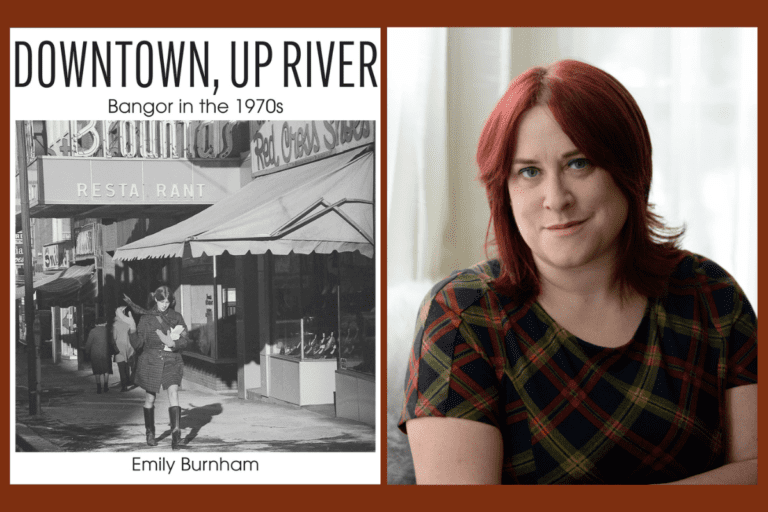

In his upcoming book, the Bangor Daily News writer Emily Burnham paints a picture of the Queen City half a century ago. Through more than 150 images, many from the BDN photo archives, “Downtown, Up River: Bangor in the 1970s” captures Bangor at a crucial moment in its transition from its past as a lumber capital of the world to a city. it would become.

Below is an excerpt from the book, published by Islandport Press and due out Tuesday.

Don’t tell anyone, but I didn’t grow up in Bangor. I was born in 1982 and grew up in the 1990s, in a small coastal town where there wasn’t much to do except dig through the seaweed along the beach and watch the traffic roar down the road. route 1.

A day trip to Bangor was a big agreement. In Bangor, you could go to the movies and see something that hadn’t been out in three months. You could go to Pizza Hut and listen to songs on the jukebox. And if you were lucky, you got to go to the Bangor Mall, maybe buy a trendy outfit and marvel at all the people flocking to spend money.

It took us an hour to drive up the winding Penobscot River before hitting the highway to reach what, in hindsight, were quite unremarkable beige buildings filled with stuff to buy. However, when I saw this vast shopping center, I felt like I had arrived in civilization.

My 12-year-old self never knew there was anything to Bangor other than the mall, a few motels and gas stations, and an ocean of parking spaces. I never visited downtown as a kid, other than attending the Anah Shrine Circus at the Bangor Auditorium, outside which a statue of Paul Bunyan stood silently and cartoonishly surveying the river. Why would we do it? There wasn’t much there – at least not for us kids.

As an adult, I now know that Bangor once had a thriving urban core, where immigrants from Greece, Lebanon, and Russia ran bustling businesses. I now know that Bangor International Airport was once an Air Force base and that the Bangor House was a hotel so grand that it rivaled anything in Portland or Boston. I now know that a century ago, Bangor included a red light district, where loggers, sex workers and artists played and created. And centuries earlier, indigenous peoples gave a name to each meander of the river and each elevation of the landscape.

Bangor’s fascinating and proud history — buoyed by a 19th-century lumber industry that sent lumber to towns across the country to help build homes — wasn’t at the forefront for me. Neither do its residents – unpretentious and good-natured as most Mainers are, and yet strangely sophisticated too.

To me, Bangor was a series of chain restaurants and chain stores, not “a star on the edge of the night,” as Thoreau called it when he visited in the 1840s. In his day, Bangor was the last stop before the vast expanse of the northern woods; a frontier town with the cultural attributes of a much larger city.

It’s not that Bangor’s reputation as a retail and entertainment mecca came out of nowhere. Before Bangor Mall was built in a former cow pasture off Hogan Road, the economic heart of the city was downtown. Throughout the first half of the 20th century and into the 1970s, a multitude of businesses operated along downtown streets, ranging from mom-and-pop shoe stores, clothing, grocery and candy stores to large retailers like Sears, Dakin’s Sporting Goods, WT Grant. and the famous Freese Department Store, which for decades was the only escalator in eastern Maine.

Before the 1970s, shopping in downtown Bangor was a major seasonal activity for people throughout eastern, northern, and central Maine. Back-to-school shopping in August, Christmas shopping in December, and gearing up for weddings, proms, and social events the rest of the year were rites of passage for people of all ages – often followed by lunch or dinner at one of the many downtown restaurants, a drink at a bar, or perhaps even a movie or show at the Bijou, Park or Olympia theaters . For people from remote towns in the county or the Down East, Bangor was THE big city. The Hub. The Queen City.

Changes

But when I came of age in the 1990s, all that was gone. I was a small town kid and knew the mall and the interstate highway. I knew Bangor was a city with the same type of magnetism that all cities have. Almost everything that had made Bangor the Queen City—the theaters and bars, the gangsters and the loggers, the grocers and tailors—had been erased, in the name of what otherwise intelligent people considered progress. This progress manifested itself in the form of the era of urban renewal.

I didn’t learn the meaning of urban renewal – a word spat with disgust by local historians – until I moved to Bangor permanently in 2007 to work full time at the Bangor Daily News, although I had lived in the area since 2000. At that time, downtown Bangor was in the early stages of a revitalization effort – still far from today’s bustling, growing scene – and I quickly understood why he had to rebuild himself in the first place.

If you’re a Bangor native or have lived in the city long enough, you may know that beginning in the late 1950s, the city government, with money from the federal government, is embarking on a large-scale plan to eliminate slums and dangerous old buildings. . The stated intention was to create a cleaner, safer and neater downtown.

Like many other cities across the country, Bangor leaders listened to federal officials, who sold the idea that automobile-centric urban cores with functional, tidy buildings were far preferable to tangle of streets and alleys and the mosaic of wooden buildings along the Kenduskeag. Flow.

The main arguments – that these wooden buildings posed dangerous fire hazards and that automobile traffic was the main economic driver – did not fit the very nature of Bangor, always a place where the past rubbed shoulders with the present. Bangor was an old river town, but in the postwar industrial spirit of the 1950s and early 1960s, city leaders wanted it to be a city of the future. And this future city included neither buildings, nor alleys, nor the vibrant hodgepodge of small businesses that historically operated there.

In the decade between 1964 (when voters narrowly approved the project) and 1974 (when the federal urban renewal program was replaced by federal community development grants), the Bangor Urban Renewal Authority demolished or demolished over a hundred acres of buildings and streets. Although a handful of new buildings were constructed on these suddenly empty lots, many other lots remained empty, creating a scarred landscape and a greater eyesore than what was there to begin with.

Gone is the huge old town hall on Hammond Street, replaced by a parking lot. Gone is the Bijou Theater, replaced by a parking lot. Gone is the dense maze of buildings along the creek, which housed countless businesses over the years, replaced by nondescript office buildings or, you guessed it, parking lots.

Tenement-style homes along the Penobscot River were also demolished and replaced with open lots or large apartment complexes. The inhabitants of these houses were largely displaced to the fringes of the city. The city of the future of Bangor had no poor people, although many of them still lived there.

Fortunately, many historic buildings along Main, Columbia, and Central streets were saved, as were a few along Exchange and State streets. Today, these buildings are a central part of downtown Bangor’s charm. In the aftermath of this destructive era, Bangor developed strong historic preservation ordinances – an excessive correction, at first, but one that fortunately spared many valuable architectural features from further destruction.

It took decades of effort by the local population to rebuild what it took only a few years to destroy. This effort only really began in the early 2000s and continues today. The Bangor I know and love in 2023, with its thriving small business community, nightlife, and vibrant arts scene, came about through the hard work of many people, who realized what had been lost and what was possible.

And yet, despite the physical destruction in that short time, much of what made Bangor unique never disappeared: its grit, its colorful history, its strange mix of highs and lows, its mythical days of logging and its indigenous heritage. Nor the most important resource a city has: its inhabitants.