Professor COM’s book highlights a little-known hero of the Armenian genocide

Asa Jennings was a failed Methodist minister from a small town in upstate New York, working for the YMCA in Smyrna, Turkey, in 1922, when he saved a quarter of a million Christians from death in the brutal final chapter of the Armenian genocide.

“An individual, a guy with no wallet, who had a minor position at the YMCA, came forward and organized this amazing rescue,” says Lou Ureneck, who spent four years researching and writing Jennings’ story. “One of the things I hope this book does is give America another hero. People should know about Asa Jennings’ work.

The journalism professor from the College of Communication will read an excerpt from his book, The Great Fire: An American’s mission to save the victims of the first genocide of the 20th century (Ecco, 2015) tonight, Tuesday May 19, at the Harvard Book Store in Cambridge at 7 p.m. The book was published last month to coincide with the 100th anniversary of the start of the genocide. The persistence of history can be seen in the continuing controversy over the use of the word “genocide” and the persecution of Christian minorities in other Muslim countries in the Middle East.

Beginning in 1915, the Ottoman government began the systematic elimination of its Armenian minority, as well as Greek and other Christian minorities, in Turkey, killing perhaps three million people and driving many more from the country . The book makes clear that the massacre was a ten-year genocide of Christians, beginning in 1912, and not the commonly described two-year Armenian genocide, from 1915 to 1917.

Smyrna, known today as Izmir, was a cosmopolitan port under Greek rule, where Greeks, Turks, Armenians, Jews and Europeans did business in relative peace. But after Turkish armed forces defeated the Greeks in September 1922, they began a religious cleansing, with executions and arrests triggering mob violence, rape and looting.

In a frantic effort to escape, hundreds of thousands of terrified Christians fled to the quayside along the harbor in the hope of finding safe passage. The Turks responded by setting fire to the city. “Half a million people, crowded onto a narrow strip of sidewalk, about a mile and a half or two miles long, as a giant fire bears down on them, essentially pushing them into the sea,” says Ureneck . “And many of them jumped into the sea, either trying to swim to the ships or committing suicide, or their clothes and packages caught fire.”

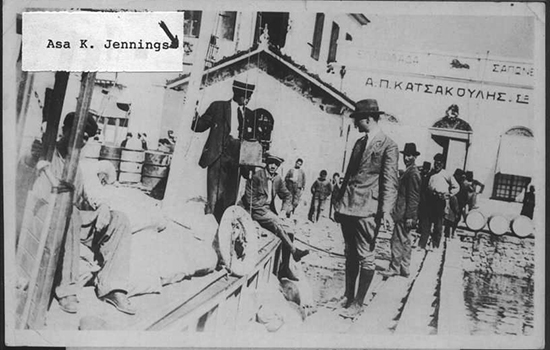

Jennings, a mild-mannered little boy with back problems, had managed to get his family on a boat with other Americans, but he stayed behind to try to help several thousand refugees in shelters along the dock. Horrified by what he saw, he first bribed an Italian ship captain to keep people away from the shelters. Then he hatched an even more ambitious plan, securing a flotilla of empty Greek merchant ships to save thousands more.

American sailors watching the massacre on the dock were pushed to intervene where they could, pulling drowning refugees from the water and stopping individual acts of violence. But beyond protecting its own citizens, the U.S. government, which has growing trade ties with Turkey, was unwilling to get involved, especially so soon after a costly war. The highest-ranking American officer in the region, Admiral Mark Bristol, was playing tennis outside Constantinople (now Istanbul) while Smyrna burned.

But the Navy man on the scene in Smyrna, Lt. Commander Halsey Powell, moved to help Jennings execute the evacuation even though it was against his orders. Much of this operation took place quietly, behind the scenes, but at a crucial moment Powell aimed his ship’s big guns at the Turkish army. This gesture alone was enough to “transform the situation,” Ureneck says.

The author of Backcast: Fatherhood, fly fishing and river travel in the heart of Alaska And Cabin: Two brothers, a dream and five acres in Maine, Ureneck had a long and highly honored career as a newspaper editor (Portland Press Herald, Maine Sunday Telegram, And Philadelphia Inquirer) before joining the University. He first read a brief mention of Jennings in a book about Smyrna perhaps 30 years ago.

“I wondered who this man was,” he said. “He saved a lot of lives, and it seemed to me to be one of the great untold stories in American history.”

He stuck with the idea and began serious research four years ago, visiting libraries and archives in Washington, London and many other cities. Some of his best sources were U.S. Navy reports written by officers there. He visited some of Jennings’ churches in New York, where the pastor had little or no memory, and met Jennings’ grandson and studied his diary. He also visited many of the book’s locations during four trips to Turkey.

“I had been reading about this horrible event for a long time, and finally I found myself there,” Ureneck says. “Today, the modern city of Izmir is a metropolis of concrete and glass. Ancient Smyrna was destroyed and a modern city grew up in its place. But it’s still easy to imagine. The Point is still there, the place where the Turkish machine guns kept the refugees from escaping is still there, the pier is still there… there are these artifacts that will remind you of the old story. There was so much suffering.

Jennings was actually recognized for a brief period after the burning of Smyrna, but his story and that of the genocide fell victim to a State Department campaign to protect diplomatic and trade relations with an ascendant Turkey.

Ureneck found that many people in Turkey cling to a different version of events, often blaming Armenians for starting the fire.

“What I discovered is that these years constitute a black hole in Turkish history for the Turkish people,” he says. “History as it is taught in Turkey is shaped by ideology.”

In general, “the people of Izmir know that there was a fire, they know that Greeks and Armenians lived there and they know that there was a population exchange. But they don’t know much else about what happened,” Ureneck says. “People asked me a lot of questions about what I knew and where did I learn it?… I think there are more and more educated classes in Turkey who want to know. »

He says Armenian attempts to bring this history to the forefront – as well as the pope’s recent declaration calling it a genocide – have changed people’s understanding.

“I think the world became aware of what happened in Asia Minor during those years,” Ureneck says. “When will Turkey stop denying it? I have no idea. But it is clear that there are many people in Turkey who would like to know the truth, who are ready to admit the truth, who want to know the facts. So I think that one day Turkey will end up reconciling itself with its history. But it is not an easy thing for any country to admit that it participated in a genocide.”

Lou Ureneck will read The big fire at the Harvard Book Store, 1256 Massachusetts Ave., Harvard Square, Cambridge, today, Tuesday, May 19, at 7 p.m. Via public transportation, take an MBTA Red Line train to Harvard Square.

Explore related topics: