Culture is the expression of how we perceive the world, how we interpret our environment and evaluate the people we encounter. Our personal interpretation of what we perceive is guided by factors as diverse as affections, convictions, preconceived notions, beliefs and values.

In other words, culture is about positioning oneself within one’s environment and community. But at the same time, culture can also be about distancing or separating from individuals or communities.

How culture provides direction and stability

When culture helps us position ourselves in our environment, it orients us and creates identities. However, just like cultures, identities are not very stable.

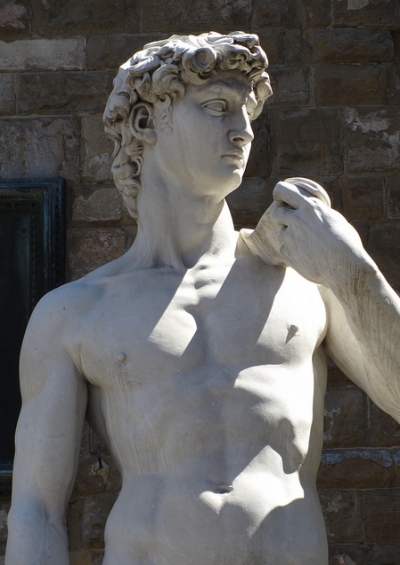

Material culture and cultural materials are so powerful and attractive to us because they are potentially more stable than human identities and social communities.

Buildings and monuments can last hundreds or even thousands of years. A precious family heirloom can be passed down from generation to generation, a ring, a watch, a painting, a handwritten letter.

And although cultural objects have no meaning in themselves, they are literally what we make of them and what we see in them.

It is for this reason that cultural objects – whether movable or immovable – give us a sense of stability, duration and lasting values, which is what many human beings aspire to, especially in times of increasing uncertainty.

Furthermore, cultural objects are often expressions of success, prosperity, or success. They are tangible and visible proof that a company has the resources, capabilities and expertise to produce these objects.

Culture and otherness

Cultural objects always and invariably refer to the past and evoke history. In fact, they constitute the material anchor of all our stories about the past. Thus, cultural objects help us create lasting identities. They frame historical narratives and are material witnesses to past greatness or failure. For some, they even embody values and beliefs.

When cultural objects are seen by communities as representing something special, something linked to the identity chosen by that community, they become heritage, cultural heritage.

As much as cultural heritage is an expression of identity for any community, it is also a material expression of difference for anyone who does not belong to that community.

In this case, cultural heritage and culture as a whole can be seen as a symbol of the “other”, or even as a threat to one’s own identity. It is through culture, particularly through cultural heritage, that “otherness” becomes palpable and differences can be emphasized and reinforced, or attenuated, mediated or overcome, as the case may be.

Cultural objects as beacons of conflict and war

This is why, throughout history, cultural heritage has been a target during wars and periods of pronounced power asymmetries, such as imperial or colonial rule.

At the same time, culture and cultural heritage are powerful instruments of rehabilitation in post-conflict societies. So when you destroy or displace the culture of a community, you erase its history, you deny its achievements, you take away its common point of reference, its orientation.

But there’s something else: by destroying or displacing a community’s cultural heritage, you also reduce its chances of sustainable development, cultural diversity, rehabilitation and reconciliation after conflict.

Human history is replete with examples of the deliberate destruction of cultural heritage as a strategy of war. The first recorded cases date back to ancient Mesopotamia, the latest being the acts of cultural cleansing committed by Daesh in Iraq and Syria.

Dealing with the problem of travel

Additionally, power asymmetries in the late 19th and early 20th centuries led to the movement of large numbers of imported cultural objects to Europe and North America. This was done with the aim of researching and creating “universal” museums.

Not all of these movements were illegal or violent, as is often claimed. But it is true that we are still far from understanding in detail under what circumstances these objects were moved and what their future status could be.

Yet there is no doubt that the destruction and displacement of cultural objects is equally damaging to any affected society.

Today, as we become more aware of the social, political and economic power of culture and cultural heritage, we must do all we can to protect, promote and share cultural heritage.

It is by protecting and sharing culture that we enable orientation and identification. Culture is synonymous with diversity. When we promote culture, we promote tolerance, the ability to accept what is proper and embrace the other.

At all times in human history, culture has been an instrument of rehabilitation and reconciliation. Caring for their cultural heritage allows communities to overcome their differences and strengthen social cohesion.

Reconciliation beyond borders

In countries like Iraq and Syria, the rehabilitation of pre-Islamic cultural heritage in particular will provide an opportunity to promote much-needed processes of dialogue and reconciliation across social and confessional boundaries.

What does all this mean for us, our way of treating culture and our responsibility to protect cultural heritage? Naturally, the answers to this question will vary depending on expertise and abilities.

At the institutional level, expert institutions like the Museum of the Ancient Near East at the Pergamon Museum can use their considerable expertise in the field of archaeological cultural heritage to contribute to its protection through:

• capacity building projects

• research into illicit trafficking of cultural objects

• the development of procedures and standards for 3D digitization of archaeological heritage, and

• awareness-raising actions.

Establish accountability and transparency

At the same time, museums created by moving cultural objects into the past must make every effort to establish accountability and transparency about the history of their collections.

States have the responsibility to provide adequate legal frameworks for the protection of cultural heritage, including effective laws against illicit trafficking of cultural property.

Last but not least, the international community has a duty to provide assistance to countries that do not have the means to protect or care for their cultural heritage. This is particularly true in conflict or disaster situations.

A practical example

A good example of an innovative initiative is the international public-private partnership ALIPH, “the International Alliance for the Protection of Cultural Heritage in Conflict Zones”.

Initiated by the governments of France and the United Arab Emirates in March 2017, the ALIPH global fund will certainly set new standards in financial support for emergency actions and long-term research in the field of heritage protection cultural.

At a time when pluralism, freedom of expression, democracy, human rights and equal development opportunities are under threat around the world, we need culture and heritage more than ever cultural.

Culture and cultural heritage are not just a “symptom” of strong and resilient societies. Culture and cultural heritage are the key to strong and resilient societies.