We all know what dog tags are: those little oval discs on a chain that military personnel wear to identify themselves in combat. But have you ever wondered how and when this tradition began, and why they are called dog tags?

We did some research to find the answers.

Origins of the nickname “Dog Tag”

According to the Army Historical Foundation, the term “dog tag” was first coined by newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst. In 1936, Hearst wanted to undermine support for President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal. He had heard that the new Social Security Administration was considering distributing nameplates for personal identification. According to the SSA, Hearst called them “dog tags” similar to those used in the military.

Other supposed origins of the nickname include World War II conscripts who called them dog tags because they claimed they were treated like dogs. Another rumor said it was because the tags looked like the metal tag on a dog’s collar.

Whatever the origin of the nickname, the concept of the name tag originated long before that.

Civil War Concerns

Unofficially, identification tags appeared during the Civil War because soldiers feared that no one would be able to identify them if they died. They were terrified of being buried in unmarked graves, so they found different ways to avoid this. Some marked their clothes with stencils or pinned paper labels. Others used old coins or pieces of round lead or copper. According to the Marine Corps, some men carved their names on pieces of wood tied around their necks.

Those who could afford it purchased engraved metal tags from nongovernmental sellers and canteen merchants, sellers who followed armies during the war. Historical resources show that in 1862, a New Yorker named John Kennedy offered to make thousands of engraved records for soldiers, but the War Department refused.

By the end of the Civil War, more than 40 percent of the Union Army’s dead were unidentified. To put this into perspective, consider this: of the more than 17,000 soldiers buried in Vicksburg National Cemeterythe largest Union cemetery in the United States, nearly 13,000 of these graves are marked as unknown.

The outcome of the war showed that concerns about identification were well founded and the practice of making identification discs became widespread.

Make it official

The first official request to equip the military with identification tags occurred in 1899, at the end of the Spanish-American War. Army Chaplain Charles C. Pierce – who was in charge of the Army Mortuary and Identification Bureau in the Philippines – recommended that the Army equip all soldiers with circular discs to identify those who were seriously injured or killed in combat.

It took a few years, but in December 1906, the Army issued a general order requiring soldiers to wear aluminum disc-shaped identification tags. Half-dollar tags were stamped with a soldier’s name, rank, company, and regiment or corps, and they were attached to a cord or chain that passed around the neck. The tags were worn under the field uniform.

The order was changed in July 1916, when a second disk was to be suspended from the first by a short string or chain. The first label was to remain with the body, while the second was for keeping records of funeral services. The tags were given to enlisted men, but officers had to purchase them.

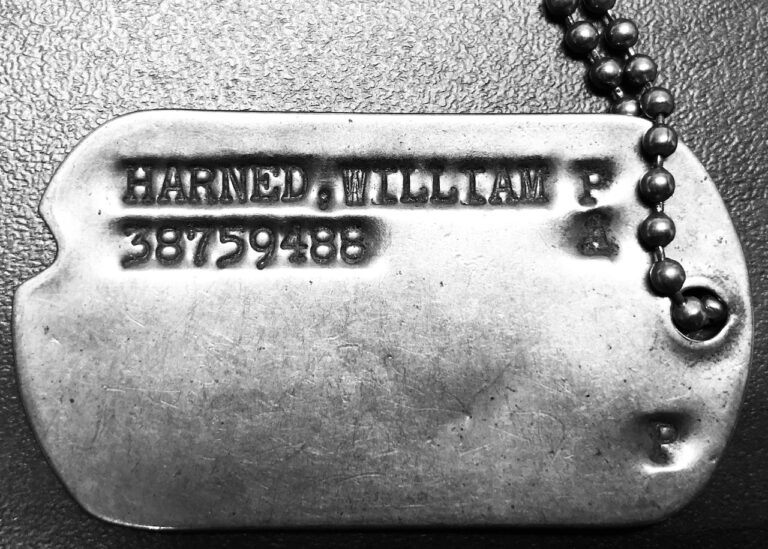

The Navy did not require identification tags until May 1917. At that time, all American combat troops were required to wear them. Exact size specifications were put in place and the tags also included each man’s Army-issued serial number. Towards the end of World War I, American expeditionary forces in Europe added religious symbols to the labels – C for Catholic, H for Hebrew and P for Protestant – but these markings did not remain after the war.

Slight differences

During World War I, Navy labels were a little different than Army labels. Made of monel – a group of nickel alloys – they had the letters “USN” engraved on them using a specific process involving printer ink, heat and nitric acid. If you were enlisted, the engraving included your date of birth and enlistment, while that of officers included their date of appointment. The biggest difference was the engraved imprint of each sailor’s right index finger on the back, intended to protect against fraud, accident or misuse.

According to the Naval History and Heritage Command, identification tags were not used between World War I and World War II. They were reinstated in May 1941, but the engraving process was then replaced by mechanical stamping.

Meanwhile, Marines had been required to wear identification tags since late 1916. Their styles were a mix of army and navy styles.

The Second World War

During World War II, military identification tags were considered an official part of the uniform and had evolved into the uniform size and shape they have today: a rounded rectangle of nickel-copper alloy .

Each was mechanically stamped with your name, rank, service number, blood type and religion, if desired. A name and emergency notification address were initially on these, but they were removed at the end of the war. They also included a “T” for those who were vaccinated against tetanus, but by the 1950s this was also eliminated.

During World War II, Navy tags no longer included the fingerprint. By the end of the war, they also included the second chain that the army had established decades before.

At that time, all military tags had a notch on one end. Historians say the notch was there because of the type of machine used to stamp the labels. In the 1970s these machines were replaced, so the labels issued today are now smooth on both sides.

Identity plates today

Regulations have varied as to whether the two labels must remain together or be separate. In 1959, the procedure was changed to keep both dog tags with the service member in the event of death. But in Vietnam, the initial regulation reverted to take one label and leave the other.

For the Marines, the size of a person’s gas mask was eventually included on the labels.

In 1969, the military began switching from serial numbers to Social Security numbers. This lasted for about 45 years until 2015, when the military began remove social security numbers tags and replacing them with each soldier’s Department of Defense identification number. The move helped protect soldiers’ personal information and helped protect them from identity theft.

Considerable technological advances have been made since Vietnam, including the ability to use DNA to identify remains. But despite this progress, dog tags are still issued to military personnel today. They are a reminder of America’s efforts to honor all who served, especially those who made the ultimate sacrifice.