ATHENS — Pericles himself may be calling, but Rishi Sunak isn’t answering the phone. This is the diplomatic dynamic currently playing out between London and Athens as the bitter struggle over the Elgin Marbles intensifies.

This phase began when conservative Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis told the BBC earlier this week that retaining the sculptures that once adorned the Parthenon in Greece but have been in Britain for more than 200 years amounted to ” cut the Mona Lisa. half.” To say Mr Sunak was not amused by the comparison would be an understatement.

The British prime minister quickly canceled a high-profile meeting between the two leaders that was scheduled for Tuesday at Downing Street. Then, during Prime Minister’s Questions on Wednesday, Mr Sunak took the extraordinary step of saying Mr Mitsotakis was seeking to “make a case” for the controversial marbles.

For Mr. Mitsotakis, the return of the sculptures to Greece is a question of “reunification” and not of “ownership”. However, his choice to speak on the subject during his visit to London earlier this week, and on a matter of national pride for the British and Greeks, seems to have backfired.

Here again, there is a twist: Mr Mitsotakis learned of the cancellation while meeting Labor Party leader Sir Keir Starmer on Monday evening. Labor leads Mr Sunak’s Conservatives in a recent survey by 20 percentage points. Mr Sunak was reportedly unhappy that his Greek counterpart preferred to meet the opposition Labor leader first.

Mr Starmer also took a different approach to Mr Sunak. The work would have been more open to agreement on the Elgin Marbles. Not that frustration isn’t beneficial both ways. Unusually for a Greek prime minister, Mr Mitsotakis publicly expressed his “dismay” at the abrupt cancellation of the meeting.

On social media, he said: “Greece’s positions on the issue of the Parthenon sculptures are well known. I hoped to have the opportunity to also discuss it with my British counterpart, as well as the major challenges of the international moment: Gaza, Ukraine, the climate crisis, migration.

With a touch of mockery, he added: “Anyone who believes in the correctness and justice of his positions is never afraid of opposing arguments. »

Initially, the British government said Mr Sunak was simply unavailable, although the lunchtime meeting had been scheduled in advance. A spokesperson later attempted to ease friction, saying that “the relationship between the UK and Greece is extremely important. From our joint work in NATO, to tackling common challenges such as illegal migration, to joint efforts to resolve the crisis in the Middle East and the war in Ukraine.

Many Greeks remain skeptical. Some Greek officials, quoted anonymously in Greek newspapers, said Mr Sunak was essentially treating with disdain an elected leader of a democratic country “as opposed to himself who was in effect an appointed prime minister”. For them, it was “a mistake that Sunak will have to face sooner or later”.

Mr Sunak’s decision to reject Mr Mitsotakis can also be interpreted as a defense of what has become, over the years, part of British as well as Greek cultural heritage. There were of course urban activities of all kinds atop the Acropolis long before the City of London existed, but displays of antiquities from around the world are part of what makes the British capital and British Museum its cosmopolitan appeal.

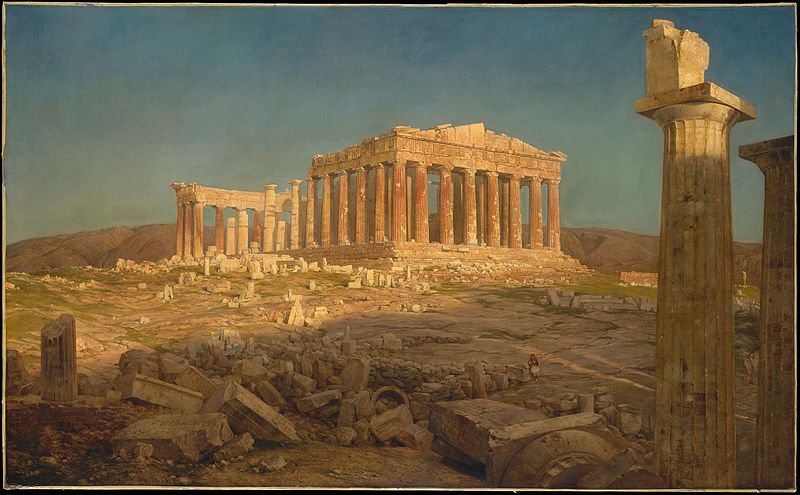

The dispute over the Elgin Marbles has long been an open wound in Anglo-Greek relations. Between 1801 and 1804, while Greece was ruled by the Ottoman Empire, Lord Elgin, the British ambassador to Constantinople, ordered his agents to remove many sculptures from the Parthenon, causing – at least from the Greek perspective – a considerable number of sculptures. damage in the process.

In 1806 the sculptures were shipped to Britain and ten years later the English government purchased them. Since then, they have been a centerpiece of the British Museum, in the Bloomsbury district of London.

However, Greece considers this a theft and maintains that the sculptures must be returned to their place of origin, Athens. For their part, the British claim that Elgin’s moves were made with the permission of the Ottoman Turks, although whether this agreement met the norms of international law, even in those distant times, remains controversial.

Interestingly, on the same day that Mr. Mitsotakis met Mr. Starmer in London, the brash new leader of the Greek left-wing opposition, Stefanos Kasselakis, was invited to a private lunch at the residence of the American ambassador to Greece, George Tsounis. The meeting, specific details of which were not disclosed, could have attracted more media attention if Mr. Mitsotakis had not been in Britain.

The chances of the marbles leaving London in the near future are not great and relations between London and Greece are durable enough to withstand the current shock. On Tuesday, Greek government spokesman Pavlos Marinakis publicly stated that Athens did not want the row to take the form of a generalized crisis in Greek-British relations.

Yet with a general election looming in Britain and the changing political landscape in Greece, it is almost certain that ancient culture and modern politics will clash again in the new year. And that finally someone will quote, once again, Lord Byron’s denunciation of his own countrymen: “Cursed be the hour when they left their island, / And once more your unfortunate gored breast , / And removed thy shrinking gods to the northern climes. abhorred! »