Every morning last summer, Stanford senior Madeleine “Elle” Ota donned heavy scuba gear and dove to the bottom of the Mediterranean Sea to excavate the remains of an ancient Roman shipwreck.

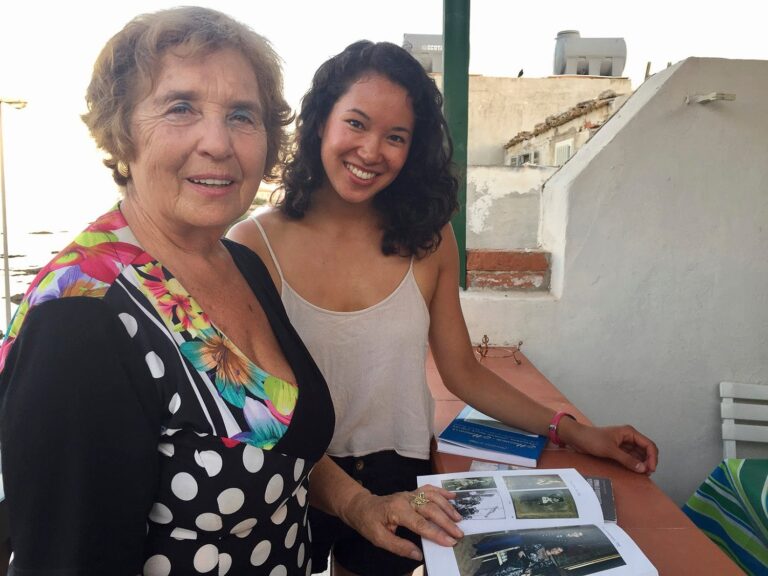

Stanford students Madeleine Ota, left, and May Peterson search underwater the ancient remains of a 6th-century Roman shipwreck near the coast of Marzamemi, Italy. (Image credit: Marzamemi Maritime Heritage Project)

Back on land, Ota brought her search team a plastic basket filled with pieces of pottery and stones she had found. And then, with a notebook in hand and a translator at her side, Ota wandered into the nearby Sicilian village to ask locals what the artifacts of the region’s ancient civilizations said about their local history and sense of place. today’s identity.

It was a typical day for Ota during his time abroad in southeastern Sicily, Italy. She was there to help excavate a 6th century Roman shipwreck on behalf of the Marzamemi Maritime Heritage Projectan archaeological effort led by Stanford assistant professor of classical sciences Justin Leidwanger since 2012. This research, combined with interviews with local residents, formed Ota’s undergraduate thesis project.

“Archaeology is not just about digging into the past, but also about preserving things for the present,” said Ota, who has a double major in classics and archeology and will pursue a master’s degree in anthropology through the Stanford joint program. “But I think too often archaeologists do their work and look for artifacts without considering how those objects affect the people who live around archaeological sites. And I wanted to emphasize archeology to the people it touches.

Ota is one of several Stanford students who have accompanied Leidwanger and other researchers each summer to Marzamemi, a small village on the southeast coast, to excavate a Roman ship that sank in the 600s while he was transporting materials to build a church.

Ota dove 25 feet underwater to help search for pieces of marble and other stones for the church’s construction. Researchers say the Roman Emperor Justinian sent ships like these to help promote Christianity across the Mediterranean.

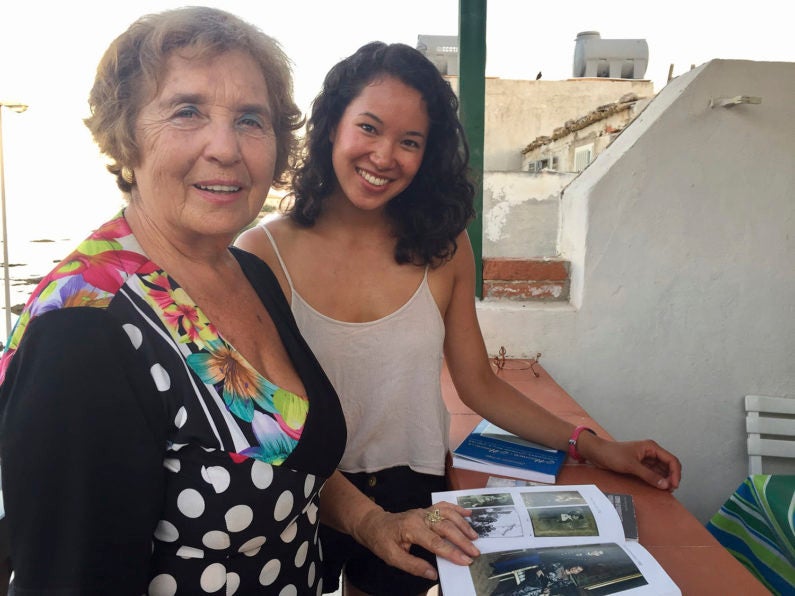

Stanford student Madeleine Ota, right, interviews Giuseppina Aliffi, a local historian in Marzamemi, Italy, as part of her summer 2017 research project. (Image credit: Courtesy of Madeleine Ota)

During her six weeks in Sicily, Ota visited the historic Marzamemi Square to talk with locals about how the objects she discovered – remnants of an ancient civilization – might affect them today . She asked residents questions such as “Do you think the classical world is important to the history of this region?” “” and “What aspects of Marzamemi’s story are most important to you?” » In total, she interviewed nearly 40 residents.

Throughout its history, Sicily has been colonized by numerous groups across the Mediterranean Sea.

But Ota found that most people in the Marzamemi region felt their history and way of life was linked to ancient Greek culture rather than that of the Romans, for example, who are often associated with Italy.

“This part of Sicily is truly the crossroads of the Mediterranean, with influences from Northern Europe, North Africa, Spain, Greece, Italy and others,” Leidwanger said. “It’s a place where you can choose your cultural influence. So why do people connect to different aspects of this past, and what don’t they connect to?

Locals Ota spoke with said they believed they inherited their maritime practices, moral values and dialect from the ancient Greeks. Some of them highlighted the historical importance of Syracuse, a famous Greek city founded in the 8th century BC, about 48 km from Marzamemi.

“Everyone I spoke to had the idea that their history began with the Greeks, even though many natives lived in Sicily before that time,” Ota said. “It’s been really interesting to understand how Greek history plays into Marzamemi’s past.”

Ota said it is important for archaeologists to understand how people today construct their identities in relation to the ancient artifacts and ruins around them.

I think if we can better learn how to manage cultural heritage on a global scale and foster understanding of each person’s origins, we can build a lot of respect and collaboration between individuals.

Madeleine Ota

Stanford senior

“I believe we have a responsibility not only to the materials themselves, but also to the modern populations they affect,” Ota said. “Studying classical heritage in the context of modern communities can help us understand how the world engages with the classical past and how archaeologists can handle these materials in positive and ethical ways. »

Leidwanger said Ota’s work will help his team continue its public outreach efforts in the region. In addition to the excavation work, the Marzamemi Maritime Heritage Project partners with the local community for heritage preservation and tourism in the region. For example, Leidwanger is working on a multimedia exhibit for communities across the Mediterranean to show what maritime travel was like hundreds of years ago.

“It’s been exciting to watch Elle’s project develop,” Leidwanger said. “She has done remarkable work and her work will guide us as we continue to develop links between local communities and our archaeological work. »

Ota is interning at UNESCO in Paris this summer and she said she hopes to continue working on different heritage projects around the world to bring people from different backgrounds together. She will return to Stanford in the fall to complete a master’s degree.

“Many conflicts in this world are caused by people not understanding each other and their past,” Ota said. “I think if we can better learn how to manage cultural heritage on a global scale and foster understanding of each person’s origins, we can build a lot of respect and collaboration between individuals. »