Skype co-founder and Swedish entrepreneur Niklas Zennstrom speaking at an event in Dublin. (Reuters)

America’s entrepreneurial spirit is one of the things that, in theory, is supposed to make us a great country. At least that’s the case if you listen to most politicians. But how do we actually stack up against the rest of the world when it comes to starting our own businesses?

In fact, we are not really exceptional.

We have a lower business creation rate than Sweden (and that of Israel and Italy…)

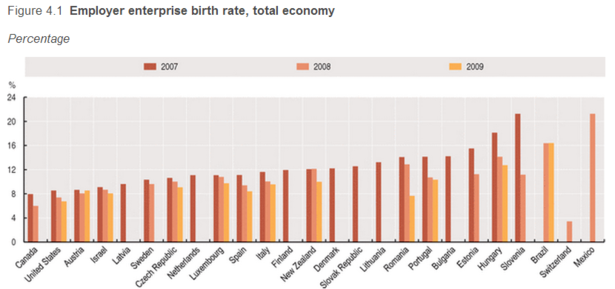

Entrepreneurship still remains a fuzzy area of economic research and (as you will soon see) using different standards to measure it can yield radically different results. But a popular approach among economists is to count the number of new businesses with paid employees that start up each year, then divide them by the number of businesses already operating. THE Organization for Economic Cooperation and Developmentan international research organization specializing in side-by-side comparisons between different economies, calls this percentage the “employee business creation rate.” Others just call it the startup rate. But whatever you call this measure, the United States scores pretty low in this area. For example, we are second to last on the OECD graph below, which covers the years 2007 to 2009.

But hey, at least we beat Canada.

There is not much in common between the countries that outperform us. Sweden is a winter wonderland and socialist. Brazil is the growth engine of the tropics. Israel has a giant public sector, but prides itself on its tech scene. Italy and Spain are the Latin countries that could cause the euro to fall. All told, it’s difficult to draw general conclusions about why all of these countries finish ahead of the United States. Countries that do better by this measure tend to be poorer, which may simply mean that it is easier for them to expand since they start with a smaller business base. However, this does not explain our ranking compared to rich countries like Sweden, Austria or the Netherlands.

Cutting-edge ideas and entrepreneurs.

See full coverage

New businesses don’t account for a large portion of our jobs

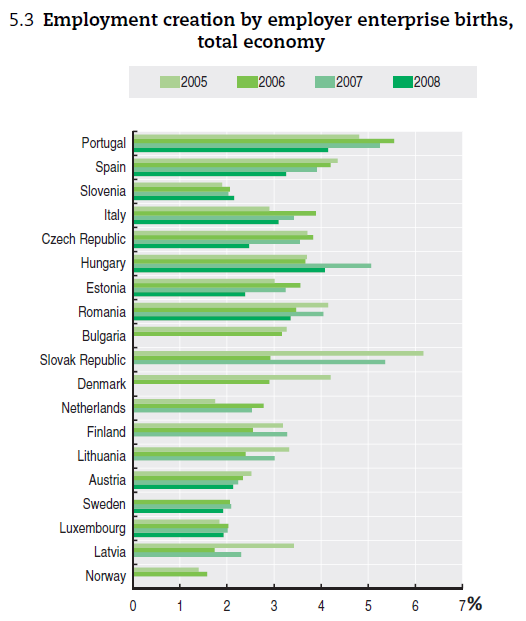

The United States produces proportionately more large start-ups than other countries, according to the OECD, and new companies have a much better than average chance of succeeding. survive at least two years here. But they do not seem to play a particularly important role in job creation. According to Marion Ewing Kauffman Foundation, new businesses accounted for about 3 percent of all jobs in the United States in 2005. In 2008, that figure was closer to 2 percent. Either way, this would put us in the middle or bottom of the OECD rankings shown below, putting us in the range of Finland and Sweden.

In short, start-ups with employees don’t make up a particularly large part of the American business landscape, nor do they create significantly more jobs here than anywhere else. What makes this situation even more remarkable is that, unlike some other countries, the United States has many, many small businesses where the only “employee” is also the owner. Freelancers, consultants, individual landscapers and others often incorporate for liability and tax purposes. As the OECD points out, this should boost our business creation rate.

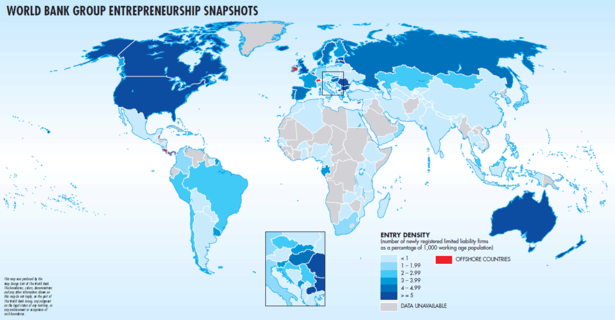

There are some studies of global entrepreneurship in which the United States leads the pack. When the World Bank calculated the average number of newly registered limited liability companies around the world between 2005 and 2009, it found that we had one of the highest rates of business formation per 1,000 population, among those Canada, Australia and the United Kingdom (as shown in the map below, where the darker blue a country is, the more new businesses are created there).

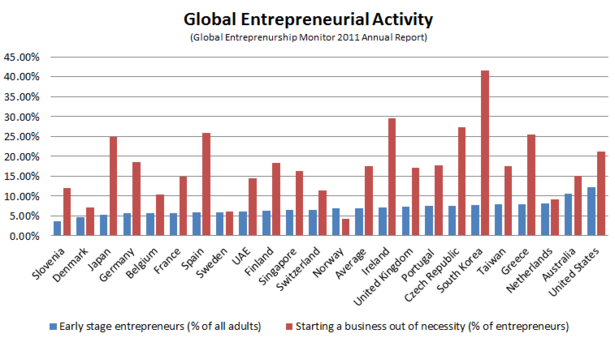

The United States also ranks first among advanced countries in entrepreneurial activity in the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor rankings. 2011 annual report, which makes estimates on the creation of start-ups around the world, based on a survey of 140,000 people. They find that about 12% of U.S. adults run businesses that are less than three and a half years old, compared to an average of 6.9% in other so-called “innovation-driven” economies. One reason this study might produce such different results than the OECD is that it considers any type of business, whether it pays its employees or not, as entrepreneurial activity. This is a big problem in the United States, where about three-quarters of all businesses have no payroll. These businesses are often owned by self-employed people who have not needed to incorporate.

Americans start businesses out of desperation

Which brings us to one of the saddest realities of American entrepreneurship. According to GEM’s findings, a very high percentage of new business owners in the United States say they started their own business not because they had a great, innovative idea or because they really wanted to be their own boss, but out of necessity. There is a disconcertingly large group of Americans who went to work for themselves only because no one else would hire them.

This fact is illustrated below. The blue bars track entrepreneurship rates among all adults. The red lines track the percentage of entrepreneurs who started their business because they had no other options. In the United States, these entrepreneurs make up about 21% of the total, putting us in a league with Greece, Spain, Ireland, and conglomerate cultures like Japan and South Korea.

Wait! you’ve probably already said it. So far, we’ve only talked about the sheer amount of startups America produces compared to other countries. What about the wonderful innovations they come up with?

Our young companies are not particularly innovative

And you would be right. Some of the world’s most forward-thinking startups call Silicon Valley, New York, Boston and Austin, Texas home, in part because we have the backers to support them. According to the OECD, the United States ranks second overall in venture capital invested as a percentage of GDP, which puts us between Israel in first place and Sweden in third place. In pure dollars, we dwarf everyone. That said, it’s not clear that all this money floating around makes our start-ups much more creative. The OECD ranks us ninth out of 22 for the number of start-ups under five years old that issue patents, adjusted for the size of our economy (Denmark leads on this measure).

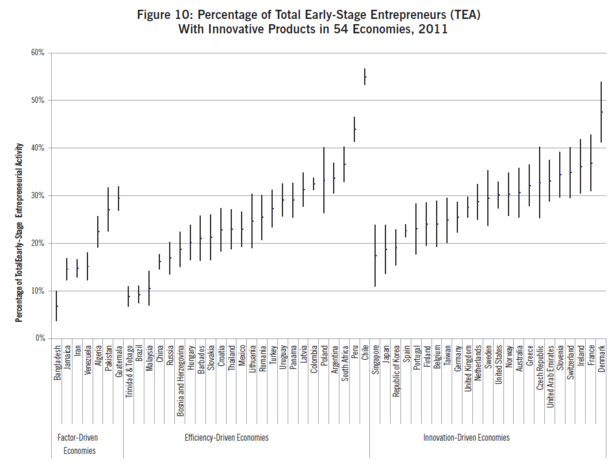

Our entrepreneurs also don’t seem to consider themselves particularly innovative. About thirty percent of new business owners told GEM that they were bringing something to market that qualified as an innovative product, putting us in the middle of the advanced economy pack (on the right in the chart below, on which you can click for a much larger version). . This result could be because the United States already has a large number of companies. For the purposes of the survey, an innovation simply meant something new to the local market, meaning that a large Jewish grocery store, for example, could be considered an innovation in Taiwan, but not in the United States. Here again, France also has a lot of companies, and they surpass us. The results certainly give us no reason to believe that American start-ups systematically innovate more than their international cousins.

Maybe this all seems a little nitpicky. We are therefore not the most entrepreneurial nation. Our start-ups are therefore not incontestably the most innovative. Americans still have a fairly strong, if weakening, tradition of starting businesses from scratch and trying to support those that do. But here’s what’s important to remember: we don’t have a monopoly on entrepreneurship. Many other economies – all with different tax structures, safety nets and regulatory regimes – seem just as exceptional as us.