The Greek Orthodox Church, the merchant class that created the revolutionary organization of brothers Filiki Eteria, Alexander and Demetrios Ypsilantis, inspired the successful outbreak of Greek independence in 1821. Fortunes were lost. A genocide of the Christian population was experienced by invading the Ottomans. The result: independence.

The Orthodox Church became the only institution to function in Greek territory under Ottoman rule. They perpetuated the memory of the Christian Byzantine Empire. Primary and higher education created a sense of identity, taking on a secular and political role.1 Their leaders played a role in the Revolution of 1821.

It is not politically correct to state this fact: it was only through the Greek Orthodox Church that young men were able to gain education and rise through the priesthood during centuries of Ottoman slavery. The martyr statue of Patriarch Gregory V, originally from Dimitsana, dominates the central square. We visited his family home and Germanos III of Old Patras from the outside. THE Orthodox Metropolitan of Patras Germanos III (1771-1826), was born Georgios Gotzias. He played an important role in the Greek revolution of 1821, exercising diplomatic and political activity.

Palion Patron Germanos was born in DimitsanaNorth West Arcadia, Peloponnese. Before his consecration as Metropolitan of Patras by Patriarch Gregory Vhe had served as a priest and Protosyngellus (Chancellor) in Smyrna. Bishop Germanos played an important role in the Filiki Eteria. Dimitsana is linked to the Greeks of Smyrna, Constantinople, Cyprus, the secret Greek society of Filiki Eteria and Russia. Catherine the Great’s “Greek Plan” in the 1770s, which culminated in the Battle of Chesma (Tseme) off Chios, immortalized in the seascapes of Ivan Aivazovsky, was supported by the Greeks of Dimitsana and the Peloponnese.2

The phrase I constantly hear in America in 2021 is “Follow the money” and learn the truth. On the 200th The anniversary of Greece’s independence, it explains the forces that forged independence from the crippling slavery of the Ottoman Turkish Empire.

Thanks for reading Hellenic News of America

The Alexander S. Onassis Public Benefit Foundation (United States) describes the rise of Greek business in “From Byzantium to Modern Greece: Hellenic Art in Adversity, 1453-1830.” The 18thth century was crucial for the Greek business world. A different perception of what was really happening and the alternatives. Large Greek cities are transforming into economic capitals, such as Smyrna and Thessaloniki. The commercial center developed in Ioannina, Arta, Patras, Chios and Heraklion. After 1774, Greek merchants controlled much of domestic and foreign trade through the authority of the authorities, the Ottoman Empire’s system of privileges with Western Europe, and the Greek communities of Vienna, Trieste, Livorno, and Odessa.

The merchants’ experience with the West and the reality of Greek life made them aware of the weakness of the economy of their Ottoman masters. The authoritarianism of the authorities, a system of privileges and a climate of uncertainty hindered capital investment. Manufacturers who had moved beyond the cottage industry stage were prevented from developing into real industrial units.

The French consul in Thessalonica, Félix de Deaujour noted: “Despotism makes fortunes ephemeral, because…no one cares to gain what he can lose. » Greek merchants realized that the “occupation” was hindering economic development. They consolidated Greek identity, without supporting the ESTABLISHMENT. This contributed to a revolutionary national ideology.3

The Greek merchant class inspired the creation of the “Filiki Eteria”, (Friendly brotherhood). It was a Greek revolutionary secret society founded by merchants in Odessa in 1814 to overthrow Ottoman rule in southeastern Europe and establish an independent Greek state.

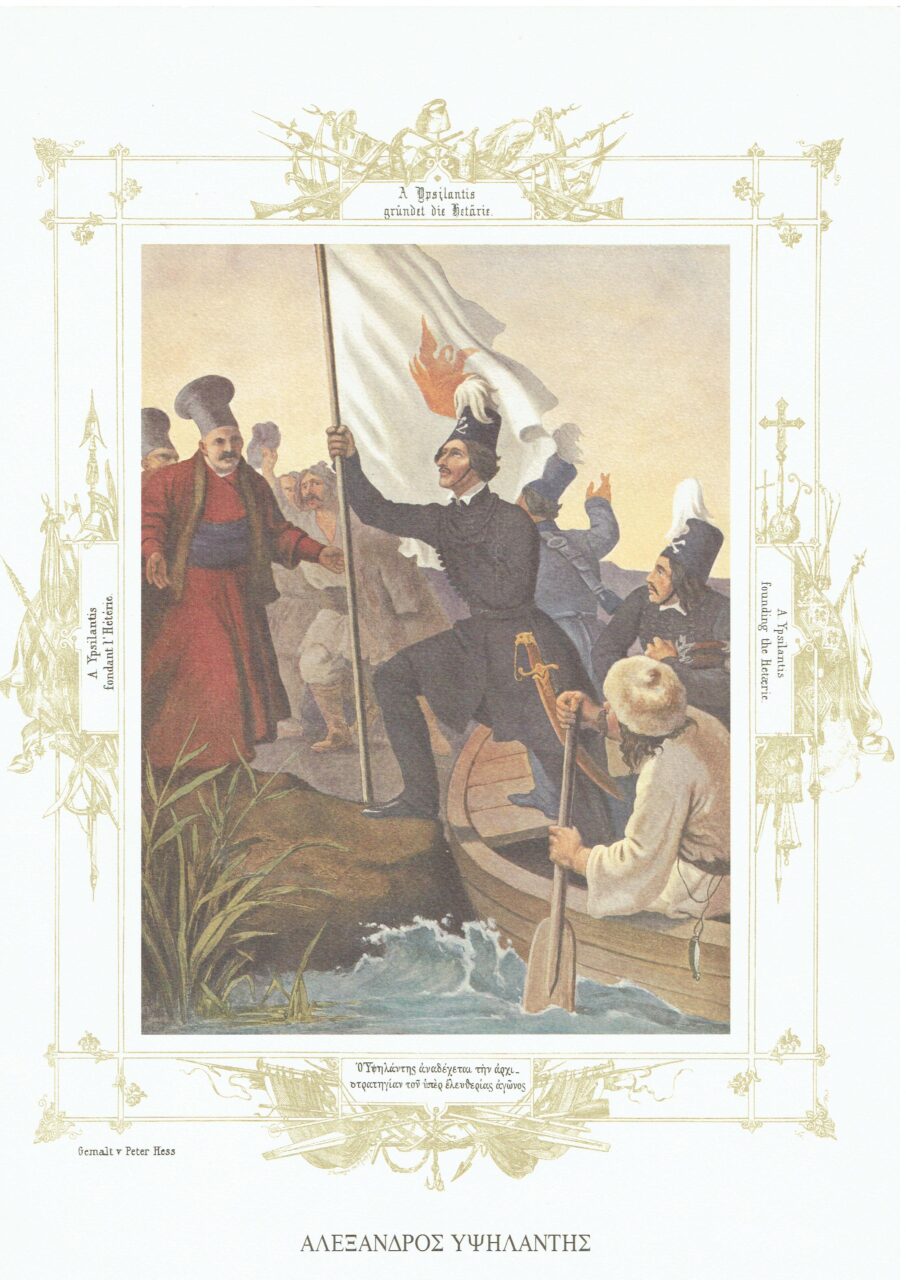

The company’s claim to Russian support and the romanticism of its commitment (each member swears “irreconcilable hatred against the tyrants of my country”) have attracted thousands to its ranks. Although some recruits believed that the company was secretly run by the Russian emperor’s foreign minister, the Greek Ioannis, Count Kapodistrias, it was Alexandre Ypsilantisofficer in the Russian army, who accepted leadership in 1820.”4

Alexander and Demetrios Ypsilantis were descendants of the Komnenos dynasty of emperors of Byzantium, dating from 1200. “The Ypsilantis were descended from palace families who followed Alexios Komnenos Doukas, when Constantinople fell to the Latins (1204), to establish the empire of Trabzon, Pont. The Ypsilantis family had expertise in diplomacy. They were interpreters, ministers, rulers of Wallachia and Moldavia (Romania). The journalist Spiros Melas of the newspaper “Eleftheros Vimas” explained in 1930: “But in all their dramatic life, which took place between two flashes of honor from the Sultan and the sword of the executioner, they never lost sight Greece: they served it with their spirit and their blood.5

Alexander Ypsilantis planned uprisings in the Danubian principalities as well as in the Peloponnese and the Greek islands. Ypsilantis launched the revolt in the spring of 1821. The Romanian peasants, however, did not join his forces; the Russian emperor Alexander I repudiated him, and the Turks quickly defeated him. The enterprise mainly resulted in putting an end to the reign of the Greek Phanariotes in Moldova And Wallachia.6 The Ypsilantis uprising was crushed on June 7, 1821. But it spread across the entire Greek continent.7 The sacrifice of Alexandros Ypsilantis inspired the Greeks to fight and gain their independence.

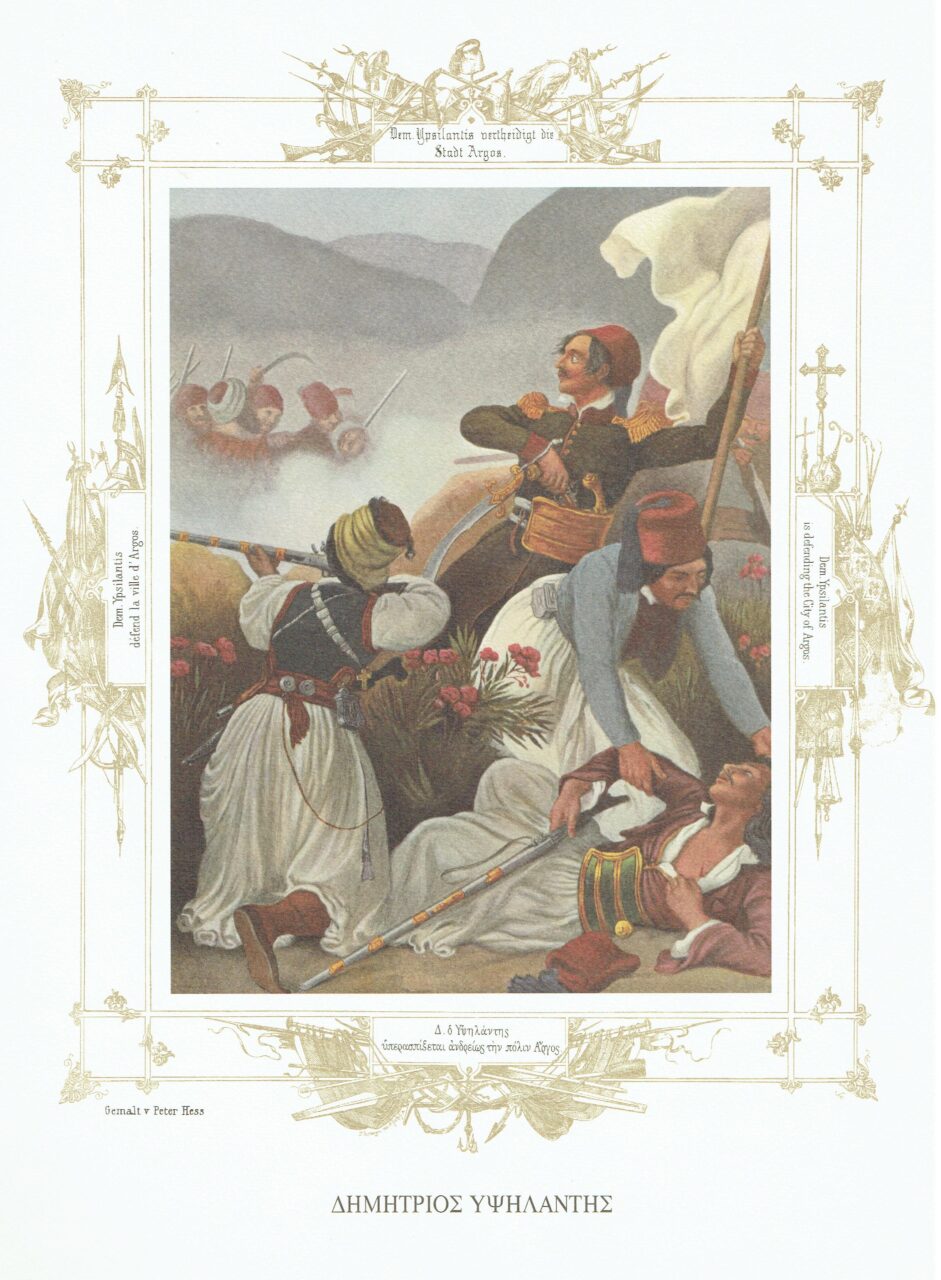

The heroism of Demetrios Ypsilantis, Alexander’s brother, inspired Westerners in Michigan. In 1825, Ypsilanti, a town in Michigan, “was named for the Greek patriot general Demetrius Ypsilanti, a heroic figure in the battle the Greeks were waging against Turkish tyranny – a struggle for freedom that many Americans compared to our own.” With three hundred men, Ypsilanti held the citadel of Argos for three days against an army of thirty thousand men; once his supplies were exhausted, he and his entire command boldly fled behind enemy lines without losing a single man.8 A bust of Demetrios Ypsilanti stands between the American and Greek flags at the foot of the famous Ypsilanti Water Tower.9 The Church, commercial interests, Filiki Eteria, the Ypsilanti Revolt, and the self-sacrifice of the ordinary Greek set the stage for Greek independence. European governments changed their neutrality upon seeing the success of Greek independence fighters, who challenged the governments.

The references:

- Alexander S. Onassis Public Benefit Foundation (United States), “From Byzantium to Modern Greece: Hellenic Art in Adversity, 1453-1830.” New York, 2005, p22

2. https://greekamericanexperience.wordpress.com/2018/07/10/on-the-

3. Alexander S. Onassis Public Benefit Foundation (United States), p. 25.

4. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Philiki-Etaireia

6. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Philiki-Etaireia

7. Alexander S. Onassis Public Benefit Foundation (United States), p. 26.

8. https://cityofypsilanti.com/325/Ypsilanti-History

10. Peter Von Hess. Revolution of the nation of 1821: 40 lithographs, Delta, Athens, 1996.

11 https://www.ypsireal.com/blog/post/ypsilanti-water-tower/

Connections: https://greekamericanexperience.wordpress.com/2017/09/15/on-the-road-in-greece-pavlos-vrellis-greek-history-museum/