Padilla called the claimants to the front of the room. At first they stood uncertain on the stage, like teenagers auditioning for a play. Then, slowly, they moved towards the rows of wooden desks. I saw one of them, a young man in an army green football t-shirt that said ‘Support our troops’, offered a group of legionnaires. “I will take land from non-Romans and give it to you, grant you citizenship,” he promised them. As more and more students left their seats and began to negotiate, offers and counter-offers reverberated against the stone walls. Not everyone took him seriously. At one point, another requester approached a blue-eyed legionnaire wearing a lacrosse sweater to ask what it would take to gain his support. “I just want to stand up for my right to party,” he replied. “Can I have a statue erected for my mother? someone else asked. A stocky blond student kept charging at the front of the room and proposing that they “kill everyone”. But Padilla seemed energized by the chaos. He went from group to group, sowing discord. “Why let someone else take over?” he asked a student. If you are a soldier or a peasant dissatisfied with imperial governance, he said to another, how do you resist? “What types of alliances can you negotiate? »

Over the next 40 minutes, there were speeches, votes, broken promises and bloody conflicts. Several people were murdered. Eventually it seemed that two factions merged and a count was called. The young man in the football shirt won the empire by seven votes and Padilla returned to the podium. “What I want to think about in the next few weeks,” he tells them, “is how we can tell the story of the early Roman Empire not just through a variety of sources but through a variety of people.” He asked students to reflect on the lives behind the identities he assigned to them and how those lives had been shaped by the machinery of empire which, through military conquest, slavery and trade, creates the conditions for a large-scale movement of human beings.

Once the students left the room, accompanied by the rustle of umbrellas and raincoat synthetics, I asked Padilla why he hadn’t assigned a slave role. Tracing his fingers along the top of his head, he told me he had thought about it. It troubled him that he could “reconstitute a form of silence” by avoiding enslaved characters, given that slavery was “arguably the most pervasive feature of the Roman imperial system”. As a historian, he knew that the assets at the disposal of the four wealthy senators – the 100 million sesterces he had given them to support one suitor over another – would have been made up largely of the slaves who worked in their mines and plowed the fields of their rural estates. Was it harmful to encourage students to imagine themselves in roles of such comfort, status and influence, when a vast majority of people in the Roman world would never have able to be a senator? But ultimately, he decided that leaving the enslaved characters out of roleplaying was an act of care. “I’m not ready yet to turn to a student and say, ‘You’re going to be a slave.'”

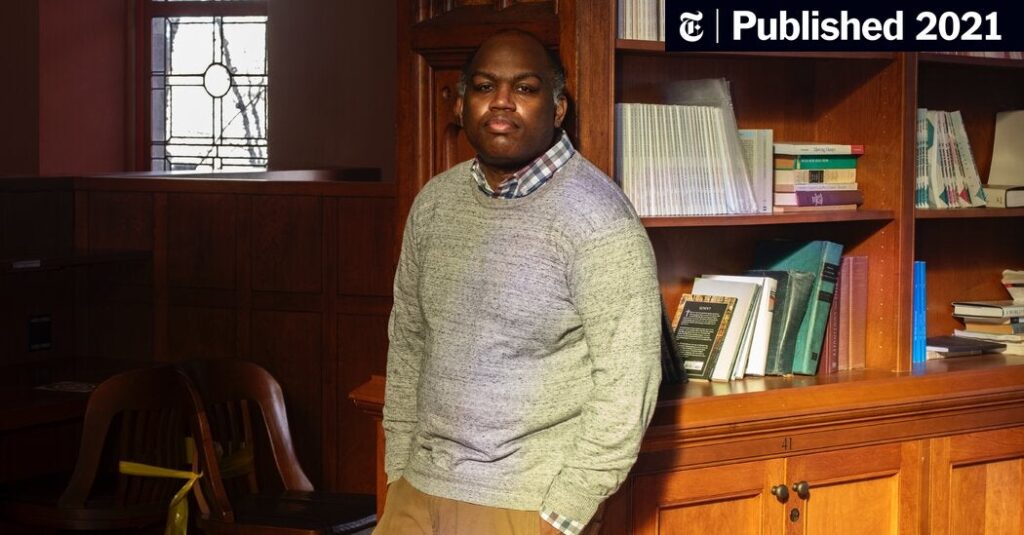

Even before the “incident”, Padilla was the target of right-wing ire because of the scathing language he uses and, many would say, because of the body he inhabits. In the aftermath of his exchange with Williams, which was covered by conservative media, Padilla received a series of racist emails. “Maybe African Studies would suit you better if you can’t hope with the reality of how advanced Europeans are,” read one. “You could understand why the wheel never made it a Sub-Saharan African, asshole. Lucky for you, your black, because you don’t have much else to offer. Breitbart posted a story accusing Padilla of “killing” classics. “If there was a realm of learning guaranteed never to be hijacked by the forces of ignorance, political correctness, identity politics, social justice, and absurdity, you might have thought that this would be the classics,” it read. “Welcome, barbarians! The gates of Rome are wide open!

Privately, even some sympathetic classics worry that Padilla’s approach will only hasten the estate’s decline. “I’ve spoken to undergraduate majors who say they’re ashamed to tell their friends they’re studying classics,” Padilla’s Princeton colleague Denis Feeney told me. “I think it’s sad.” He noted that the classical tradition has often been used for radical and disruptive ends. Civil rights movements and marginalized groups around the world have drawn on ancient texts in their struggles for equality, from African Americans to Irish Republicans to Haitian revolutionaries, who considered their leader, Toussaint L’ Opening, like a black Spartacus. The heroines of Greek tragedy – savage, righteous and destructive women like Euripides’ Medea – became symbols of patriarchal resistance for feminists like Simone de Beauvoir, and descriptions of same-sex love in the poetry of Sappho and in the Platonic dialogues gave hope and comfort to gay writers like Oscar Wilde.