Histories have played a central role in shaping the narratives that underpin the rise of nationalism. Nationalism, the ideology that emphasizes the interests and identity of a specific nation, has often been encouraged and propagated by historians who seek to establish a coherent national identity; build a feeling of unity within a people; and legitimize political and social agendas. Although historians’ contributions to the development of nationalism can be seen as both constructive and controversial, it is essential to recognize their significant impact.

Historians are the storytellers of the past. The stories they create have the power to shape collective memory and identity. By selecting and interpreting historical events and figures that resonate with the desired national identity, historians can construct a compelling narrative that reinforces the sense of belonging and shared heritage within a people.

This selective storytelling can be a powerful tool for mobilizing individuals toward a common nationalist cause. Historians often play a role in identifying and celebrating national heroes and figures. By emphasizing the achievements and contributions of individuals who embody the values and ideals of the nation, historians can create models and symbols that inspire nationalist sentiment. These heroes can serve as rallying points for national pride and unity.

The culture of historical memory is at the heart of the rise of nationalism. Historians contribute to the preservation and promotion of historical events and symbols that strengthen national identity. They often ensure that important historical milestones are remembered and commemorated, thereby reinforcing the sense of continuity and shared history among citizens.

Historians may also engage in questioning external narratives or historical narratives that undermine a nation’s identity or sovereignty. By reinterpreting historical events or offering counter-narratives, historians can help safeguard a nation’s image and defend its interests on the world stage.

Historians have considerable influence on the curricula and educational materials used to teach history to the younger generation. The way history is taught in schools can have a significant impact on the development of nationalist sentiments among students. Historians who align their work with nationalist ideals can shape the way history is presented in educational settings.

Historians have sometimes been called upon to legitimize political programs that favor nationalist goals. They can provide historical justifications for territorial expansion, cultural preservation, or the pursuit of national self-determination. This gives a veneer of historical authenticity to political actions motivated by nationalism.

It is crucial, however, to recognize that the influence of historians on nationalism is not without its drawbacks and controversies. Selective interpretation of history, glorification of certain historical figures, and suppression of alternative narratives can lead to a distorted view of the past. This, in turn, can breed exclusionary forms of nationalism that fuel conflict and divisions between diverse groups. German historians of the 19th The century, for example, gave a boost to an extremely intense nationalism which ultimately gave birth to National Socialism.

Mommsen’s political position today is confusing. He was a liberal supporter of the monarchy and a rigorous scholar whose nationalism had notes of racism. He had strong anti-French feelings and welcomed the War of 1870 as a means of liberating Germany..

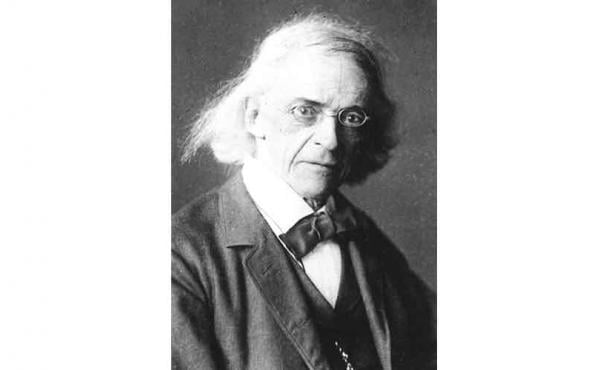

These historians, unlike their counterparts in philosophy and literature, were not focused on introspection. Instead, they were influenced by the rise of nationalism in Germany in the late 19th century. Among them, a prominent historian was Theodor Mommsen (1817-1903).

Despite humble beginnings in Garding, Schleswig (he was the son of a pastor), he studied at the University of Kiel in Holstein. His academic career took him to France and Italy, where he studied classical Roman inscriptions in depth. In 1857, he became a research professor at the Berlin Academy of Sciences and played a central role in the creation of the German Archaeological Institute. Additionally, in 1861 he became professor of Roman history at the University of Berlin.

Mommsen’s scientific contributions have been immense, with more than 1,500 published works to his credit. He was notably the pioneer of the study of epigraphy and played an important role in the creation of the sixteen-volume work Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarumfor which he himself is the author of five volumes.

Known for his dedication, he began his days at 5 a.m., often seen reading while walking. Remarkably, he had sixteen children. Two of his great-grandsons, Hans and Wolfgang, became prominent German historians. In 1902, at the age of eighty-five, Mommsen received the Nobel Prize for Literature, a rare honor for a nonfiction writer. He is the only historian to have understood it.

Beyond his academic activities, Mommsen also ventured into politics. He was a delegate to the Prussian Landtag from 1863 to 1866 and from 1873 to 1879. Subsequently, he became a delegate to the Reichstag from 1881 to 1884, initially representing the German Progress Party and later, the National Liberal Party.

Despite his fervent nationalism, he engaged in sharp disagreements with figures like Bismarck and fellow historian Heinrich von Treitschke. Her stance on nationalism was intriguing, as it differed from the right-wing perspective she eventually became.

Mommsen’s most famous work, History of Rome, published in three volumes between 1854 and 1856, consolidated its reputation as one of the greatest classics of the century. Although the work remained unfinished, it was a significant influence in its time, often compared to masterpieces such as Goethe’s. Faust and that of Schopenhauer The world as will and idea.

Notably, Mommsen’s analysis of Julius Caesar depicts him as a genius whose government was just and more democratic than the corrupt and selfish Roman Senate. As a staunch nationalist, Mommsen advocated for Caesarism, a system in which a strong and impartial ruler guaranteed a just and less corrupt form of democracy, different from other political ideologies of his time.

The book also presents an ancient concept, which would later be known as “race psychology”, used to glorify one’s country. In this case, Theodor Mommsen boldly claimed in his book that the Germans were more talented than the Greeks or Romans in terms of creativity. He expresses it by saying: “Only the Greeks and the Germans possess a natural source of artistic inspiration: while Greece brought only a few drops from the golden vase of the Muse to the fertile soil of Italy. »

Mommsen’s political position leaves us perplexed today. He was a liberal supporter of the monarchy and a rigorous scholar whose nationalism had notes of racism. He had strong anti-French feelings and welcomed the War of 1870 as a means of freeing Germany from what he saw as misguided imitation of the French.

(To be continued)

The writer is a professor at the Faculty of Liberal Arts, Beaconhouse National University, Lahore.