Citizens of modern democracies have used a variety of voting methods and technologies on election day, but how did people participate in elections in ancient times? Historians have pieced together intriguing details of Athens, one of the first and only direct democracies in the worldand the Roman Republic, a quasi-democracy where the wealthier classes exercised more influence than workers.

In Athens as in Rome, participation in the democratic process (the Greek word democracy means “power of the people”) was limited to demos, who were free male citizens. Women and slaves did not have the right to vote.

America 101: Why do we vote on the first Tuesday?

WATCH: Why do Americans vote on Tuesdays?

Representatives chosen by randomization machine

There were very few elections in Athens, because ancient Athenians did not believe elections were the most democratic way to choose officials, explains Eric Robinsonprofessor of history at Indiana University and editor of Ancient Greek democracies: readings and sources. “For a democracy to give all the power to the people to run things, and not just the rich, people had to be chosen at random. »

To decide who would serve on the Council of 500, the main governing body of Athens, the Athenians used a system known as the drawing of lots. There were 10 tribes in Athens and each tribe was responsible for providing 50 citizens to serve for a year on the Council of 500.

Each eligible citizen was given a personalized token and these tokens were inserted into a special machine called cleroterion which used long-lost technology (involving tubes and bullets) to randomly select each tribe’s contribution to the council.

WATCH: Ancient Greece on HISTORY safe

In the Assembly: one man, one vote

In Athens, all laws and legal matters were decided by the Assembly (Ekklesia), a massive democratic body in which every male citizen had a say. Of the 30,000 to 60,000 citizens of Athens, approximately 6,000 regularly attended and participated in the Assembly’s meetings.

The Assembly met in a natural hilltop amphitheater called Pnyxderived from a Greek word meaning “closely packed together”, and could accommodate between 6,000 and 13,000 people.

“The Greeks haven’t had elections in the sense that we think of them, where you vote by mail or go to a school or church to cast the ballot,” says Del Dickson , professor of political science at the University of San Francisco. Diego and author of Popular Government: An Introduction to Democracy. “You had to be physically present. This is where the word republic comes from (public thing is Latin for “a public place”). You will meet with other citizens and decide on the issues that come before the Assembly that day.

The daily agenda of the Assembly was set by the Council of 500, but all laws and government policies were then put to a vote. The vote was by show of hands and the winner was determined by nine “presidents” (proedroi). The Athenians were very careful to avoid any possibility of cheating the system.

“For example, the nine vote counters were chosen at random the morning just before the Assembly meeting, so it would be very difficult to bribe them,” says Robinson.

There were a few positions in Athens that were elected by the Assembly, the most important being those of military generals. Each year, 10 generals were elected by a simple vote for or against by the Plenary Assembly.

Stones used as secret ballots

In addition to passing laws, the Assembly rendered verdicts in all criminal and civil trials in Athens. Instead of a 12-person jury, Athenian juries numbered between 200 and 5,000 people, Dickson says. Additionally, a jury member was randomly selected to act as judge, not to have the final say, but to ensure that rules and procedures were followed.

While other types of voting took place in public, Athenian juries voted using a special type of secret ballot involving stones.

As Robinson explains, each juror was given two small stones, one solid and another with a hole in the middle. When it was time to vote, the juror approached two ballot boxes. He would drop the stone with his verdict into the first urn and throw the unused stone into the second urn. No one watching could tell which was which.

The ancient Greek word for a small stone or pebble is psephos and survives in English as “psephology,” the statistical study of elections and voting patterns.

Special elections for ostracism and exile

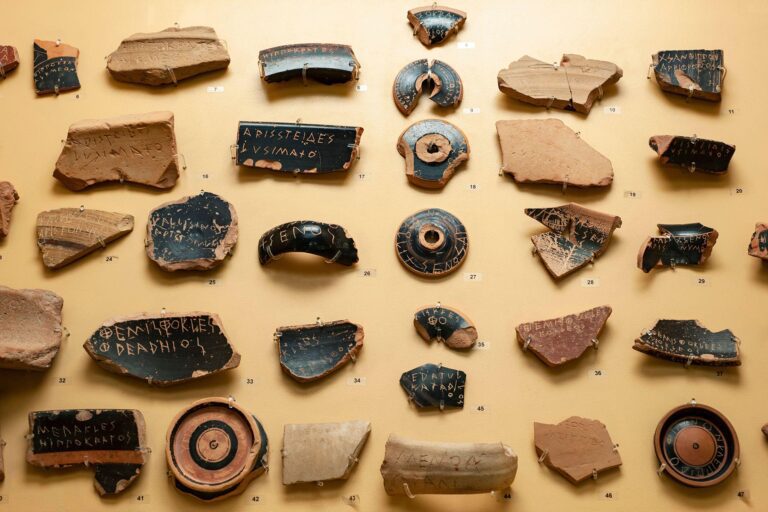

Ostraka were fragments of pottery used as ballot papers in Athens.

In Athens, if a public figure was disgraced or simply became too popular for the sake of democracy, they could be exiled for 10 years following a special “ostracism” election, a word derived from ostrakathe ancient Greek word for a pottery shard.

In an ostracism election, each member of the Assembly was given a small piece of pottery and asked to cross out the name of someone who deserved to be exiled. “If at least 6,000 people write the same name, the one with the most votes will be expelled from Athens for 10 years,” Dickson explains.

A famous example is Themistocles, an Athenian military hero of the Battle of Salamis against the Persians, who was ostracized in 472 BC and died in exile. There is evidence that Themistocles’ political enemies engraved his name on hundreds or thousands of pottery shards and distributed them to illiterate members of the Assembly.

In Sparta, an ancient “clap meter”

Athens was the largest and most powerful of the ancient Greek city-states, but each municipality practiced its own form of voting and elections, says Robinson, who wrote a book called Democracy beyond Athens.

An example is Sparta, which was not a democracy, but included some democratic elements. One of the highest governing bodies in Sparta was the Council of Elders (gerousie), composed of two Spartan kings and 28 elected officials, all over the age of 60, who would hold office for life.

“To fill the empty seats, the Spartans resorted to a particular style of shout election,” also known as cheer voting, Robinson says. “Each candidate took turns entering a large meeting room, and people shouted and cheered their approval. In another room, out of sight, the judges compared the volume of the cries to choose the winners.

Roman elections gave a “prerogative” to the rich

The Roman Republic took some of the principles of Athenian democracy, but divided the electorate by class and created a system that favored the wealthy, Dickson explains.

Instead of voting in one giant assembly like Athens, the Romans had three assemblies. The first was called the Centuriate Assembly, and this body elected the highest offices in Rome, including consuls, praetors and censors, and was the assembly responsible for declaring war.

Voting in the Centuriate Assembly began with the richest class and the counting of votes stopped as soon as a majority of the 193 members was reached. So if all the rich wanted a bill passed or a particular consul elected, they could vote as a bloc and sideline the lower classes. In Latin, the privilege of voting first was called preerogativa (translated as “to ask for one opinion before another”) and is the root of the English word prerogative.

In the other two Roman assemblies, the Tribal Assembly and the Plebeian Council, the voting order was determined by lot. “Tribes” in Athens and Rome were not based on blood or ethnicity, but on the geographic region in which you lived. In this way, the Tribal Assembly functioned similarly to the United States Senate, where each state was equally represented.

Secret votes and campaigning in the Roman Republic

Some aspects of elections in the Roman Republic are still relevant today. Voting in the assemblies began like the Athenian model, with each member of the assembly raising their hand and voting publicly. But over time, it became clear that wealthy “sponsors” were pressuring members of the Roman assembly to vote a certain way, so the vote had to be done in secret.

In 139 BC, Rome introduced a new type of secret ballot. “It was a wooden tablet with a sheet of wax on the outside,” says Robinson. “You would write your vote on the wax sheet, then place the entire tablet in an urn. The aristocracy attacked this because they lost some of their control.”

If you think election advertising is a recent nuisance, archaeologists have discovered hundreds of examples of ancient election ads and political graffiti scrawled on the walls of Pompeii. As for the official campaign, Dickson says that candidates for office in Rome were limited to a campaign season of one or two weeks, and most of it took place in person in the public square.