Millions of Americans will attend parades, fireworks and other Independence Day events Tuesday, celebrating the courage of 18th-century patriots who fought for independence from Britain and what they considered to be an unjust government. These events will also honor military personnel and those who have sacrificed in other conflicts who have helped preserve the nation’s freedom at home. 247 years of history.

It’s just one version of “patriot.” Today, the word and its variations have evolved beyond its original meaning. It has infused itself into political discourse and school curricula, with varying definitions, while being appropriated by white nationalist groups. Trying to define what a patriot is depends on who you ask.

Although the origins of the word come from ancient Greece, its basic meaning in American history is that of someone who loves their country.

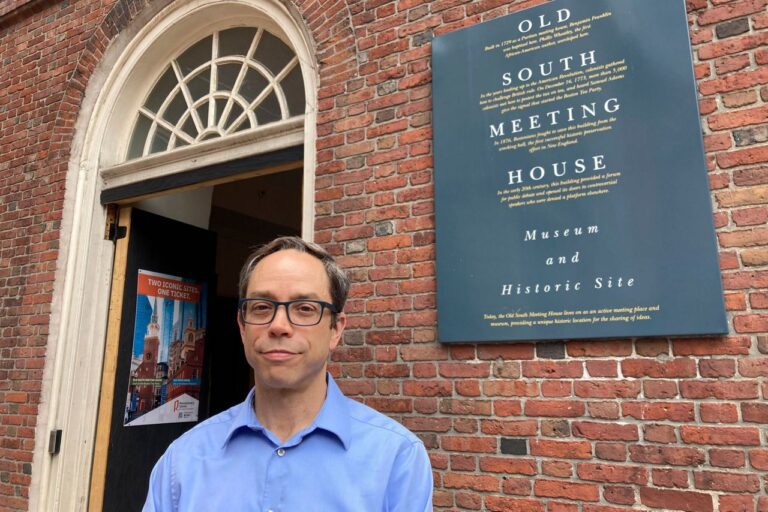

The first patriots emerged from the American Revolution, most often associated with figures such as Sam Adams and Benjamin Franklin. But slaves who advocated abolition and members of indigenous communities trying to reclaim or maintain sovereignty also considered themselves patriots, said Nathaniel Sheidley, president and CEO of Revolutionary Spaces in Boston. The group manages the Old State House and the Old South Meeting House, which played a central role in the revolution.

“They participated in the American Revolution. There were workers campaigning for their voices to be heard in the political process,” Sheidley said.

The mark of patriotism, he said, was then “a feeling of self-sacrifice, of caring more for one’s neighbors and other members of the community than for oneself.”

In some ways, the vision of patriotism has always paralleled civic and ethnic nationalism, historians say.

“Patriotism really depends on which American describes themselves as patriotic and which version or vision of the country they hold dear,” said Matthew Delmont, a historian at Dartmouth.

Opposition to the government and dissent are common features of the definition of patriotism, he said. He cited the example of black servicemen who fought in World War II and championed civil rights when they returned. They also considered themselves patriots.

“For them, part of patriotism meant not only winning the war, but then going home and trying to change America, trying to continue to fight for civil rights and to have real freedom and democracy here in the United States ” said Delmont.

For many white Americans who consider themselves patriotic, “they view other white Americans as the true definition of Americans,” Delmont said.

Far-right and extremist groups have been characterized by American motifs and the term “patriot” since at least the early 20th century, when the second Ku Klux Klan became known for its slogan “100% Americanism said lead researcher Mark Pitcavage. at the Anti-Defamation League’s Center on Extremism.

By the 1990s, so many anti-government and militia groups used the term to describe themselves that watchdog groups called it the ” Patriot movement.”

This extremist wave, which included the Oklahoma City bombing Timothy McVeighfaded in the late 1990s and early 2000s. But many such groups resurfaced when Barack Obama became president, according to the Southern Poverty Law Centerwho closely followed the movement.

Since then, many right-wing groups have called themselves “patriots” by fighting against electoral processes, LGBTQ+ rights, vaccines, immigration, diversity programs in schools and much more. Former President Donald Trump frequently refers to his supporters as “patriots.”

The term functions as a branding tool because many Americans have a positive association with “patriot,” reminiscent of the Revolutionary War soldiers who defied the odds to found the country, said Kurt Braddock, professor of American university and researcher at the Institute of Polarization and Research. Extremism Research and Innovation Laboratory.

One example is the white supremacist militia Patriot Front, which researchers say uses patriotism as a kind of camouflage to hide racist and bigoted values. Some white nationalist groups may genuinely see themselves as opposing tyranny — even if they are actually “very selective” about which parts of the Constitution they want to defend, Braddock said.

Gaines Foster, a historian at Louisiana State University, said that at one time patriotism was seen as a civic nationalism that believed “that you are an American because you believe in democracy, you believe in l equality, you believe in opportunities. In other words, you believe certain things about how government works, and that’s a very inclusive view.

He said that the violent January 6, 2021, attack on the US Capitol was the most dramatic example of how views of patriotism have changed in recent years, claiming that “people have begun to turn less toward a commitment to democracy and more toward the idea contained in the Declaration of independence according to which there is a “right to revolt” and this becomes patriotism.

Bob Evnen has been active in Nebraska Republican politics for nearly 50 years and was instrumental a decade ago in passing a requirement that the Pledge of Allegiance be recited in schools. The measure does not require students to participate, but requires schools to set aside time each school day for the pledge to be recited.

He pushed for this engagement policy to be included in the state’s social studies curriculum standards, despite criticism from some lawmakers and civil rights organizations who called it “forced patriotism.” .

The intention, he said, is “to teach our children to become young patriots who have an intellectual understanding of the genius of this country and who feel an emotional connection to it.”

“At some point we lost that – to our detriment, I believe,” Evnen said.

Today, Evnen is Nebraska’s secretary of state who oversees elections and is sometimes the target of election conspiracy theorists – usually fellow Republicans. They made unfounded accusations election rigging across the country and often question his patriotism if he disagrees.

Evnen finds these accusations infuriating. For him, patriotism is unifying around “the idea of freedom and self-government.” He said today’s national debate over what constitutes patriotism flies in the face of reason.

“These are nothing more than personal attacks aimed at shutting down debate,” he said. “Anyone who deviates from orthodoxy is labeled unpatriotic.”

In Idaho, Gov. Brad Little and Superintendent of Public Instruction Debbie Critchfield, both Republicans, announced in June that the state had purchased a new “patriotic” history supplemental curriculum that would be implemented available free of charge to all public schools.

“It is more important than ever that Idaho children learn the facts about American history from a patriotic perspective,” Little wrote on Facebook. He said the lessons will help “truly transform our students here in Idaho.”

Little’s office referred questions about the supplement to the state Department of Education.

The “America’s Story” curriculum was developed by conservative author and former Reagan-era Secretary of Education Bill Bennett. In a 2021 press release, Bennett said the program was necessary because “an anti-American ideology that radically misrepresents American history has infiltrated our education system and misled our children.”

It is difficult to compare the supplemental curriculum to lessons currently used in Idaho schools because each district selects its own texts and lesson plans.

The new curriculum emphasizes that talking about American history and teaching the subject should be done with the goal of “cultivating respect and love for your country,” Critchfield said.

“It’s not about changing history, it’s about honoring the history that we’ve had,” she said.

Democratic Rep. Chris Mathias, a member of the House Education Committee, has not yet seen the supplemental curriculum, but said history classes should teach the good and the bad and discuss – without shame – the aspects uncomfortable parts of history.

Calling a program “patriotic” suggests that others currently in use are not, he said.

“I would really like to know if that’s true,” said Mathias, who previously served in the U.S. Coast Guard. “As a veteran, I think many people disagree on what it means to be dedicated to America. I think a lot of people think blind devotion is the same thing as patriotism. I don’t know.”

___

Fields was reported in Washington, Beck in Omaha, Nebraska, and Boone in Boise, Idaho. Associated Press writers Steve LeBlanc in Boston and Linley Sanders and Ali Swenson in New York contributed to this report.

____

The Associated Press is receiving support from several private foundations to improve its explanatory coverage of elections and democracy. Learn more about AP’s Democratic Initiative here. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

Copyright 2023 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed without permission.