In many ways, the Indus Valley Civilization transformed urban life.

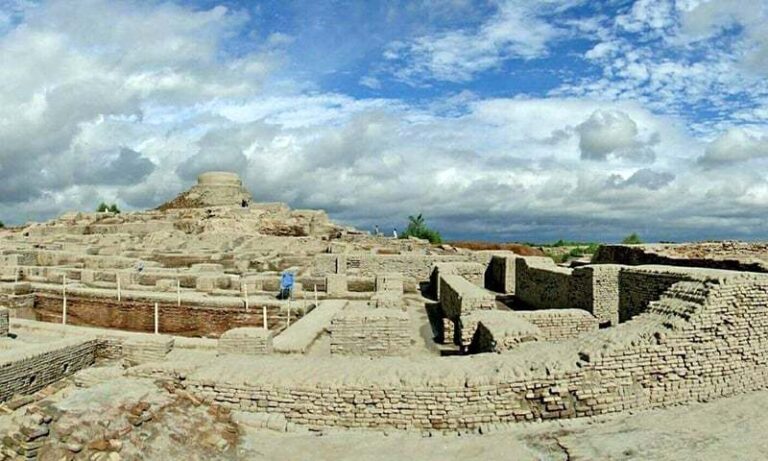

Mohenjo-Daro and Harappa, two of the most recognized cities of this ancient civilization that arose around the Punjab and Indus rivers, were the first cities in the world to have a sophisticated sewage system.

By the standards of the ancient world, these were multicultural societies where traders from Afghanistan, Persia (now Iran), Mesopotamia (now Iraq, Kuwait, Turkey and Syria) and even Egypt brought their goods.

The mighty Indus became their highway, opening the world to these cities.

But sewage isn’t the only reason these cities are unique. In all the cities of the Indus Valley Civilization, of which Mohenjo-Daro is considered the largest, there is no remains of a grand palace or special temple.

Read next: Saving the lost city of Mohenjo Daro

Rather, it is assumed that these towns had community centers, including a community swimming pool.

This has led many archaeologists and historians to hypothesize that these societies were in a much more “democratic” way than some of the other ancient cities with a palace or fort in the center of the city.

However, one must pay attention to the use of the term democratic in this context due to its contemporary connotation. It is very likely that, just like ancient Greece, this “democracy” was limited to a particular gender, class or caste.

There is also a theory that instead of a king, these cities had a priest-king who, although not a monarch, was more equal than the others in this democratic system.

Historians and archaeologists also point out that the cities of the Indus Valley Civilization were not governed by an overarching state but managed as city-states with localized governments.

The age of empires, at least in ancient India, had not yet taken root.

Rival stories

So there is much to enjoy in these ancient cities.

In India, it sometimes feels like this appreciation has been amplified to an absurd level.

In recent years, with the rise of mythological and historical fiction genres, popular writers have crafted tales of an ancient India “pure” from the “corrupting” influences of Muslims.

One imagines that this is a time when India was technologically advanced with its indigenously developed helicopters, surgeries and even bombs.

Lost in these myths is the ingenuity of simple innovations, like a sewer system that truly transformed the world.

On this side of the border, the situation is reversed. India is considered an “impure”, “uncivilized” land, which first saw the “light” with the arrival of the Muslims.

This narrative is created particularly through school textbooks, which rarely focus on the country’s pre-Islamic history.

A textbook case: Do school textbooks glorify war and martyrdom?

Even when we talk about this pre-Islamic history, it is in a certain context, to emphasize the ultimate ascendancy of Muslim civilization.

So, on both sides of the border, it seems that children are being raised with mirror images of each other.

The situation worsened in Pakistan in the 1970s under Zulfikar Ali Bhutto. By 1971, Pakistan had lost East Pakistan, which before partition had been the vanguard of the Pakistan movement.

It was claimed that the two-nation theory, Pakistan purposewas dead and dusted.

The new populist state emerging under Bhutto, instead of reflecting changing circumstances, adhered to a reactionary approach.

Related: Why is the great philosopher Kautilya not part of Pakistan’s historical consciousness?

History as a subject – which included stories of Ram, Buddha, Ashoka and Kanishka as well as Mahmoud Ghaznavi and the Mughals – was abolished and Pakistani studies was introduced, with the sole aim of inculcating a Pakistani identity.

The course seemed to shout loud and clear that the two-nation theory was not dead but had survived for thousands of years and would live forever.

All traces of pre-Islamic history were removed when the Arab commander Muhammad Bin Qasim became the “first Pakistani”.

As a new generation of leaders emerged after Bhutto, even those who defined themselves in stark opposition to him continued to promote the historical framework that had been bequeathed to them.

Political tool

In this new order that emerged, the Indus Valley Civilization acquired a unique significance, as it was not as “Hindu” as some of the other historical sites and buildings in the country.

At the time of the Indus Valley Civilization, Brahmanism, popularly associated with Hinduism, had not yet emerged.

There is indeed a popular theory, rejected by several experts on the Indus Valley Civilization, that its cities were destroyed by the Aryans of Central Asia, who ultimately laid the foundations of Brahmanism.

Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro were therefore not “Hindu” cities.

Separated from their Hindu influence, these cities became acceptable. Their archaeological excavations continued while the museums at these sites remained open.

In 1996, Aitzaz Ahsan, a senator from the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP), wrote a book: The Indus saga and the creation of Pakistanin which the implication is that the Indus Valley Civilization was always distinct from the Ganges Valley Civilization which was to emerge later in northern India – thus, in a way, the Pakistan was always meant to be separate from India.

The most recent appropriation of this story was in 2014, when PPP Chairman Bilawal Bhutto-Zardari decided to use Mohenjo-Daro as the site of the complex. Sindh Festival, a cultural event.

Sindh Festival: More than bread and circuses?

The message is clear: Pakistan’s pre-Islamic history is acceptable as long as it is separated from its Hindu influence.

This message is also clearly visible in the Taxila region, where dozens of ancient Buddhist sites are well-maintained and open to visitors.

What is missing from the charts that contain the history of these sites, however, is how they were once “Hindu” sites before they were appropriated.

The situation of Sikh historical sites has improved with several gurdwaras renovated in recent years.

Compare this to the Katas Raj, an ancient Hindu temple in the heart of Chakwal, Punjab province, built around a sacred pond believed to have been created from a tear of Shiva.

See then: Enter the Katas Raj Temples

The sacred pond has dried up several times. In November, the Supreme Court of Pakistan took suo moto action to investigate drying pond.

With Imran Khan, sworn in as Pakistan’s 22nd Prime Minister, promising a ‘New Pakistan’, there are high expectations that the state will witness a massive transformation.

However, would a transformation be experienced in this context?

Will the state led by its new Prime Minister become secure enough to recognize its Hindu past and the Indus Valley Civilization without using it as a political tool to secede from “Hindu” India?

This piece was originally published on Scroll.in and has been reproduced with permission.