In sight

Whitney Museum of American Art

Ruth Asawa through the line

September 16, 2023 – January 15, 2024

new York

Unraveling the intertwined lines and structures of the eclectic work of Ruth Asawa (1926-2013) is difficult and rewarding. The American sculptor was born in California to Japanese immigrant parents. With her family – she was one of seven children – Asawa spent sixteen months in an internment camp during World War II. There, she found herself continually drawing with whatever media was available. “Sometimes good comes from adversity,” Asawa said. “I would not be who I am today without internment, and I love who I am,” she wrote. She added: “I think (art) helped with the anger, but I didn’t know that at the time. » She had grown up on a farm, attentive to nature and the available culture of her time, watching television, attentive to the news of the day and capturing its images. At the same time, she learned to draw with both hands.

A good student and deeply intuitive practitioner, Asawa obsessively explored the paths of vision through nature, craft, history, materials (like paper folding), and drawing styles, including meandering Greek (i.e. the classic sinuous geometric pattern that can continue indefinitely), and performance and dance. As a result, she left behind a highly stylized and tightly controlled body of work that sits aptly between compulsive craftsmanship and delicately crafted fine art.

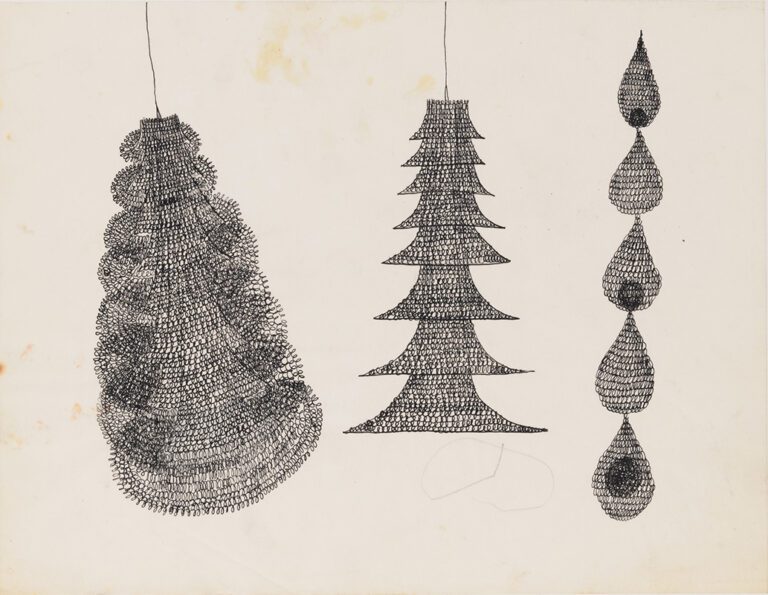

This show, Ruth Asawa through the line, on view at the Whitney through January, focuses on the artist’s drawings, collages, watercolors, prints, copperplate works, and sketchbooks, placing Asawa prominently among the artistic progeny of teachers as well important as Josef Albers, Merce Cunningham, Buckminster Fuller, and the mathematician Max Dehn, all of whom taught at the progressive experimental Black Mountain College in North Carolina, where Asawa studied in the late 1940s. Known primarily for her wire sculptures of iron in the shape of a basket, Asawa shows here his journey towards sculpture, tracing his origins via line, paper and construction. Reading his signature style, we follow his work from the inside out, through endless patterns, repetitions and associations: mind, body and matter blend with his cultural heritage and experience of the American landscape. Even her family – six children and her architect husband – helped create and inspire her practice.

Visually, we see how space creates textures and patterns where we least expect them. Asawa was more consistent than a compulsive creator. She drew every morning, working around her children and their activities so that household chores and caregiving were always part of her art. The process was everything. She layered her pigments and brushstrokes in such a way as to produce new approaches to vision at all levels. For example, in his drawing Bentwood rocker (1959-1963), composed with felt-tip pen on paper, she varies the density of tones to create a spiral movement. She used both sides of the paper not only for economy, but also to allow transparency, which resulted in depth and variety of lines, allowing the viewer to see upside down. It also shed light on his design sensibilities, showing how his mind adapts to form and function.

The scope of Asawa’s investigations was vast. She creates superb watercolor abstractions, reminiscent of certain works by Paul Klee, then finely filed sketches of characters and objects, sensitive but not sentimental. She also produced insightful portraits capturing the subtle characteristics of her subjects, including a portrait of her close friend Imogen Cunningham (1975) wearing a pearl necklace, as well as spontaneous drawings with varied effects, such as the Expressive Drawing Plane tree #12 (1959), with its strange black and brushy gestures, suggesting an inner turmoil. Particularly moving is her introspective self-portrait in ink on paper (1960), in which she captures her own absorption in the act of drawing. She is clearly in tune with her process. It was Albers, with whom Asawa was particularly close at Black Mountain, who encouraged her to be frank. As she recalls: “Some considered Albers a fascist, a dictator, because he didn’t respond to or tolerate your feelings… He wasn’t very concerned about what we felt. He cared about what we saw and what we learned to see.

Asawa was a model of intelligence and adaptability, uniting polarities such as abstraction and figuration, art and design, the natural and the artificial. The only thing missing, it seems, is technology…and that’s very refreshing.