- By Valentina Primo

- Cairo, Egypt

Image source, Tinne Van Loon

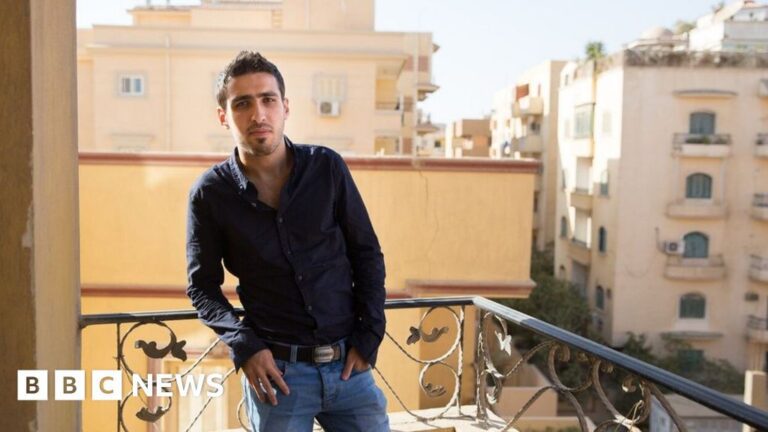

Sami Al Ahmad founded Khatwa when he was just 20 years old

Nearly half a million Syrian refugees live in Egypt, but they are not confined to camps. And thanks to this more flexible approach, many are spotting opportunities and creating new businesses.

It was the summer of 2012 when Syrian refugee Sami Al Ahmad got off a plane in a foreign country, not knowing where to go.

War had broken out in Syria and the 20-year-old dental student was faced with the choice between fleeing or joining the armed forces.

So he flew to Cairo. When he arrived, he called the only Syrian acquaintance he knew in the country.

“Come to the city of October 6,” his friend told him, referring to a satellite city of Cairo named after the start date of the 1973 Arab-Israeli war. “There is a community of Syrians here .”

Three years later, Mr Al Ahmad runs Khatwa, a leading social enterprise that has helped nearly 20,000 Syrian students access university education.

The company, created in 2013 thanks to a small initial investment from his parents, is an advice and training center for young people. It charges students $500 (£329) to process their university application, but offers free advice to help foreigners from Syria, Iraq and other Arab countries.

“When I arrived in Egypt, it was extremely difficult to continue my studies, so after I managed to enroll in university, I thought about helping others who were going through the same process,” he says.

Last January, the start-up won third prize in an entrepreneurship competition aimed at Syrian expatriates. The program – the US-based Jusoor Entrepreneurship Competition – also awarded Khatwa $15,000 (£10,000) in funding.

Image source, Tinne Van Loon

The area around Alaa Eddin Street is known as Little Damascus.

Once his office door is closed, Mr Al Ahmad heads towards the iconic Alaa Eddin Street, where two fellow businessmen are playing cards and smoking shisha in one of the cafes lined up along the pedestrian street .

Everything about the region has a Syrian flavor, from the music played in the shops to the street vendors selling spicy olives to passersby.

Image source, Tinne Van Loon

Hossam Mardini, owner of Rosto restaurant, ran a food chain in Damascus

Known as “Little Damascus”, it is located in the satellite city of Cairo, the 6th of October City, which is home to some of the nearly 500,000 Syrian refugees who have sought refuge in Egypt from the war, although 350,000 of them are not officially registered according to the UNHCR. the United Nations refugee agency.

Popular cooks

A few meters away, the area’s most famous restaurant, Rosto, is packed with cooks carving its roast chicken, known as Mashwi, for hungry customers sitting outside.

Its owner, entrepreneur Hossam Mardini, aged 36, had created a food chain of five stores of the same name in Damascus. But as fighting intensified in the streets, he was forced to sell his business and return to Egypt with the profits.

Image source, Tinne Van Loon

Ahmed Alfi says refugees ‘work incredibly hard’ because they have no safety net

Initially, only Mr. Mardini and seven of his Syrian friends decided to join forces and create a source of income. Today, the entrepreneur runs four restaurants and employs 120 Egyptian and Syrian workers, to whom he teaches the art of Syrian cuisine. “Syrian restaurants are very popular with Egyptians because our cuisine is more varied,” he explains.

Every day, after finishing work, Mr. Mardini, a married father of four, speaks to his mother in Damascus. “She doesn’t want to come to Egypt; old people generally want to die where they were born,” he says.

Unlike countries like Jordan, Egypt has not placed refugees in mass camps and allows them access to public education and healthcare. However, after the overthrow of President Mohamed Morsi and the arrival of a military government in 2013, xenophobia began to grow; local television presenters claimed that Syrians had supported the ousted president.

But despite this hostile environment, Syrian entrepreneurs have managed to exploit unexplored niches.

“Syrians are by nature traders and traders. They have always been at the crossroads, so they are very good at starting businesses,” says Egyptian Ahmed Alfi, venture capitalist and founder of the Greek Campus , Cairo’s booming hub for start-ups. -ups and technology companies located next to the iconic Tahrir Square.

And since the start of the Syrian civil war in 2011, some of the country’s biggest businessmen have moved their businesses to Egypt, with investments estimated at between $400 million and $500 million.

“Egypt has a different cross-section of the Syrian refugee population than Europe,” says Alfi. “The distance becomes a filtering process, because those who come here are not those who cross the border on foot and generally have a certain amount of capital,” he adds.

Image source, Tinne Van Loon

Omar Keshtari had created a company with several branches in Syria before fleeing to Egypt.

Walking through the Greek Campus, Omar Keshtari remembers the start-up he built in Syria. After starting it while studying at university in 2003, Mr. Keshtari established a vocational training company with branches in Aleppo, Homs, Damascus and Beirut.

But in August 2012, a bomb destroyed one of his schools outside the city and Mr. Keshtari decided it was time to leave.

Image source, Tinne Van Loon

“As an IT management expert, I would have chosen to settle in Dubai. But I had to think about my family: they would not get a visa there,” he says.

After experiencing the first two months of shock, the 35-year-old entrepreneur decided to invest his savings in the creation of Networkers, a start-up that offers computer networking, training and consulting services.

As his business continued to grow, Mr. Keshtary settled with his wife and one-month-old child in Al Rehab, a privately built town on the outskirts of Cairo where thousands of wealthy Syrian nationals live. .

A competitive advantage

“Entrepreneurship is one of the major elements of Egypt’s future, as neither the government nor big businesses will be able to absorb this population influx.” said Mr. Alfi. Its startup accelerator Flat6Labs invests in entrepreneurial ideas across the Middle East, from Morocco to Saudi Arabia.

“The competitive advantage of any refugee is their willingness to work incredibly hard, because they have no safety net,” he says. “And that’s what investors look for in an entrepreneur. You can teach them everything except desire.”

Under Egyptian law, Syrian citizens wishing to open a business in the country must legally register as foreign workers, but the process has become increasingly difficult over the past two years.

Mr Al Ahmad had to go through the procedure four times, but bureaucratic and legal hurdles did not deter him from trying again.

He says: “I wanted to create something that helps young Syrians see that we can do something.

“We are not too young to start our own business and help others,” emphasizes the 23-year-old founder, who is already planning his second business.