In this opinion piece, writer Casey Haughin-Scasny explores the virality of the recent “How Often Do You Think About the Roman Empire?” » TikTok trend in the context of story construction.

I am a woman who thinks about the Roman Empire every day. Not just the innovations of its legal system, or its monumental architecture, or even the staggering scale of its bureaucracy, but also the way its historical legacy has been written and rewritten, and the way we understand the realities of life in his past.

The recent TikTok trend is based on a simple question: women asking their male partners, family members or friends about the frequency of their ruminations about Rome. THE recorded responses range from confusion over the very term “Roman Empire” to opinions about the legitimacy of different emperors. Although there is a fair share of men who don’t think about the Roman Empire at all, the absurd comedy of the question lies in the predominance of men who don’t think about the Roman Empire at all. TO DO think of the Roman Empire, with almost reverence or obsession, unbeknownst to those close to them.

See more

The revelations, shared on TikTok, generated a deluge of content involving (predominantly white) men justifying their interest, often appealing to the “lessons” to be learned from the rise and fall of Empire, or to the importance of Rome in the modern world. . In response, women asked what the female “Roman Empire” was, that is, what women regularly think about in history that men are not aware of. Responses variedbut they mainly include the Titanic, the Triangle Shirtwaist factory fire, the Romanovs and Greek mythology.

This might be another harmless Internet fad, except for what it implies about how history is transmitted and constructed. This trend demonstrates the extent to which popular perceptions of Rome are based on an interpretation of history that many scholars now recognize as actively harmful, both to our ability to understand the ancient past and to our society as a whole.

My doctoral work in public history examines how Americans used, abused, and misinterpreted the ancient past in order to make sense of their present from the 18th century to today. I am also an archaeologist and have been participating in the excavation of a Roman villa since I was 19 years old. I teach Roman art and archaeology. Since my first introduction to Latin at the age of eleven, I have been fascinated by Rome. I would say that until then, there probably isn’t a day that goes by that I don’t think about the Roman Empire. My gender doesn’t stop me from participating in the party. Women are interested in the ancient past! Who knew?

Many people don’t do this. And there’s a reason for that.

Comments on TikTok reveal the dominance of the “great man” narratives that progressive scholars have worked so hard in recent years to supplement, challenge, and contextualize. The Roman Empire that exists in the minds of TikTok users is inherently interesting to men – and, given the way it’s talked about, why wouldn’t it be? It really is a kind of Kendom. Perhaps the Domus Aurea is the original home of the Mojo Dojo Casa.

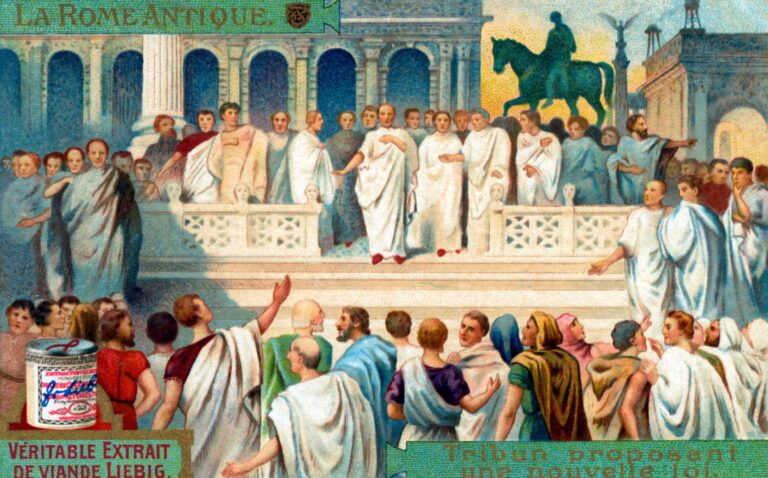

Much of the image we have built around Rome in popular culture – its place as a basis “Western civilization, the brilliance of its expansion under various male emperors and generals, the superiority of its leadership, the inevitability of its demise—rest on outdated imaginings of the ancient world. A significant part of this narrative involves androcentric interpretations of the past that emphasize the history of “great men” over the lives of the vast majority of the Empire’s citizens.

In the fascination with emperors and their propensity for conquest, we lose sight of the complex tapestry that influenced daily life in the Roman Empire. Moreover, we often risk reaffirming schools of thought very active within white supremacist circles that these “White man were naturally positioned to conquer the known world due to their innate superiority. This may seem dramatic, but it is not: there is an entire country as proof. All we have to do is look at the very foundations of America, from its governance to its laws to its architecture and much in between, to see how ideas about success and values of ancient Rome were deliberately taken, manipulated and cooked. in power structures that continue to marginalize communities to this day (the phenomenal article by Dr. Lyra D. Monteiro) “Power Structures: White Columns, White Marble, White Supremacy” is an excellent introduction to the issues discussed). Uncritical praise of Rome for all the seemingly positive things it has given us fails to understand how this legacy has been exploited historically.

I am not claiming here that Rome was some sort of egalitarian paradise where women were considered equal in the eyes of the law or in social situations. In fact, I say the opposite: Rome was an inherently unequal society, and the Pax Romana that so many people admire was built on the oppression of various demographic groups, including women. When we simply focus on the great men of these stories and romanticize imperialism, we lose the opportunity to understand how marginalized groups navigated these circumstances in ways ranging from the mundane to the extraordinary. We also lose the opportunity to ask why people from historically marginalized backgrounds would want to know about Rome now.

The tendency to relegate women’s interests in antiquity in favor of mythology, especially Greek mythology, further reveals the divisions so prevalent in popular and academic studies of ancient history. Rome presents itself as the powerful, militaristic foil to Greece’s more refined and gentler lifestyle, and mythology as a more appropriate option for women’s interests than the intricacies of rule and bloodshed. This divide is of course artificial. This has not stopped generations of people from relegating women to limited, “appropriate” fields of study, if they are allowed to be interested in antiquity, or assuming that women are incapable or uninterested in engaging with traditionally “masculine” aspects of the ancient past like epics or tactical histories. That’s not to say that women can’t be interested in mythology, that’s awesome! But there is almost a millennium to consider before accepting these divisions wholesale.

The men featured on TikTok certainly don’t consider the above heritage when they think of the Roman Empire. And that’s exactly the problem: as long as these assumptions about the past remain commonplace, the harm caused by their invocation will persist. This trend reveals how pervasive long-held assumptions about Rome are, and when these assumptions are not tested, we are able to see that consequences.

The presumption that women are not interested in these stories comes from these prejudices, but it is not innocent. Even if we put aside all the other issues I’ve discussed here, the impact of these biases on the study of antiquity is alive and well. I regularly watch male colleagues whose eyes glaze over as female colleagues talk about their work on the social histories of the Roman Empire or the pitfalls of ancient reception, while the men I meet in my life outside of academia assume that their superficial knowledge based on this imagined past is equivalent to or superior to my knowledge after a decade of training. I’ve seen too many disrespectful Q&As to not understand the consequences of men’s possessiveness over Rome and how it affects women’s ability to engage with ancient history. This article does not even touch on how these problems are magnified for researchers who occupy crossed identities as people of color, members of the LGBTQIA+ community, or disabled (like me), topics that responses on TikTok have also grappled with as the trend gains popularity. The imagination of ancient Rome affects people in more ways than just sex.

And I’m tired of it.

I’m not accusing the men featured in TikTok videos of harboring these feelings about gender, race, or imperialism. However, to ignore the subtext of this trend would be to miss an opportunity to discuss the presence of the ancient world in our modern lives, and all the baggage that comes with it. So, I have to ask: how often do you think about Why we think of the Roman Empire?