About a thousand people gathered on a beautiful morning on the National Mall the Saturday before Thanksgiving for what has become an American tradition: mourning a death on the road. With the Capitol in the background and the melody of an ice cream truck looping nearby, the crowd had gathered to remember Sarah Debbink Langenkamp, who was cycling home from her sons’ elementary school. when it was run over by a tractor-trailer.

Ms. Langenkamp was, improbably, the third State Department Foreign Service officer to die while walking or riding a bicycle in the Washington area this year. She was killed in August in the suburb of Bethesda, Maryland. Another died in July while biking in Foggy Bottom. The third, a retired foreign service officer on contract, walked near the agency’s headquarters in August. That’s more foreign service officers killed by vehicles domestically than there have been overseas this year, noted Dan Langenkamp, Ms. Langenkamp’s husband and himself an agent of the foreign Service.

“It’s maddening to me as an American diplomat,” he told the rally in his honor, “to be a person who travels around the world bragging about our record, trying to get people to think like us – to know that we are such failures on this issue.”

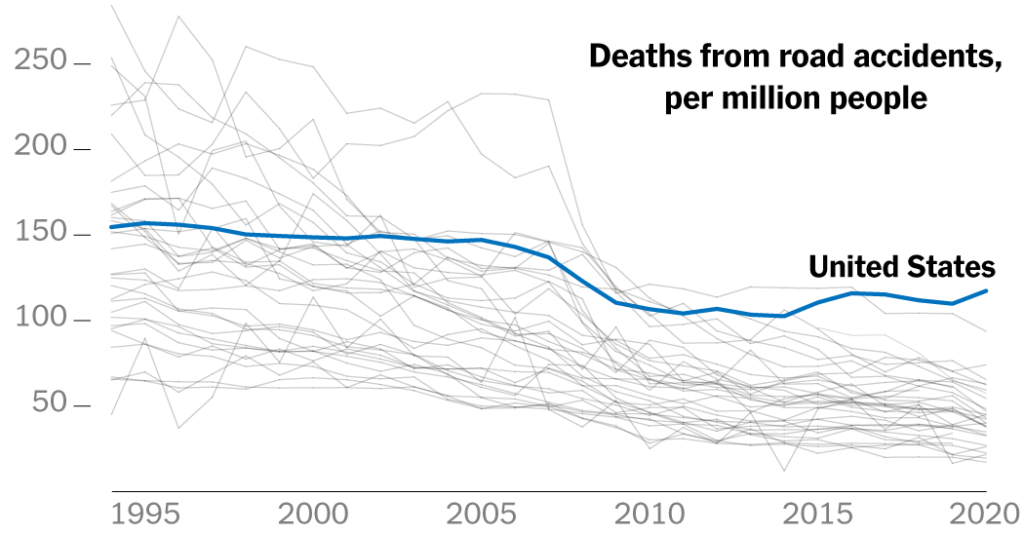

This assessment has become increasingly true. The United States has diverged over the past decade from other comparable developed countries, where road fatalities have declined. This American exception has become even more stark during the pandemic. In 2020, as car travel has plummeted around the world, road deaths have also largely declined. But in the United States, the reverse has happened. Travel refused, and deaths have increased further. Preliminary federal data suggests the number of road deaths increased further in 2021.

Security advocates and government officials lament that so many deaths are often tolerated in America as an inevitable cost of mass mobility. But periodically, the illogicality of this record becomes clearer: Americans are dying in increasing numbers even when they drive less. They are dying in increasing numbers even as roads around the world become safer. US foreign service officers leave war zones, to die on the roads around the nation’s capital.

In 2021, nearly 43,000 people died on American roads, the government estimates. And the recent increase in the number of deaths has been particularly pronounced among those the government classifies as the most vulnerable – cyclists, motorcyclists, pedestrians.

Much of the familiar explanation for America’s road safety record is a transportation system primarily designed to move cars quickly, not move people safely.

“Motor vehicles come first, highways come first, and everything else is an afterthought,” said Jennifer Homendy, chair of the National Transportation Safety Board.

This culture is rooted in state departments of transportation that have their roots in the era of interstate highway construction (and through which most federal transportation dollars flow). And it’s especially evident in Sun Belt metros like Tampa and Orlando which boomed after widespread car adoption – the roads there are among the most dangerous in the country for cyclists and pedestrians.

Trends in deaths over the past 25 years, however, cannot be explained simply by America’s history of highway development or reliance on cars. In the 1990s, the number of road deaths per capita in developed countries was significantly higher than today. And they were higher in South Korea, New Zealand and Belgium than in the United States. Then a revolution in car safety led to increased seat belt use, standard airbags and safer car frames, said Urban Institute researcher Yonah Freemark.

Deaths have declined accordingly, in the United States and around the world. But as cars became safer for the people inside, the United States did not move forward like other countries have in prioritizing people’s safety. out them.

“Other countries started to take pedestrian and cyclist injuries seriously in the 2000s – and started making them a priority in vehicle design and street design – in ways that have not. never been engaged in the United States,” Mr. Freemark said.

Other developed countries have lowered speed limits and built more protected bike lanes. They have gone faster in manufacturing standard in-vehicle technologies like automatic braking systems that detect pedestrians, and vehicle hoods that are less lethal to them. They designed roundabouts that reduce danger at intersections, where fatalities disproportionately occur.

In the United States, in contrast, over the past two decades, vehicles have become much larger and therefore more deadly to the people they hit. Many states limit the ability of local governments to set lower speed limits. The five-star federal safety rating consumers may look for when buying a car today ignores what this car could do to pedestrians.

These divergent histories mean that while the United States and France had similar per capita death rates in the 1990s, Americans today are three times more likely to die in traffic accidents. according to research by Mr. Freemark.

During this period, more and more people traveled by motorcycle and bicycle in the United States. Bike-sharing systems have spread across the country, and new modes like e-bikes and scooters have followed, accentuating the need to adapt roads – and the way users of all kinds share them – for a world that is not dominated by cars alone.

Cycling advocates said they expect the number of people to be safer as more people cycle and drivers get used to sharing the road, reducing fatalities . Instead, the opposite happened.

The pandemic has also distorted expectations. As countries adopted lockdown and social distancing rules, streets around the world were emptying. Polly Trottenberg, then New York City’s transportation commissioner, recalled a remarkable lull at the start of the pandemic when the city had zero pedestrian fatalities. She knew it couldn’t last.

“I hate to say it, but I had this anxiety that things were going to get ugly,” said Ms Trottenberg, now deputy secretary of the US Department of Transportation.

On the empty pandemic roads, it was easy to see exactly what kind of transportation infrastructure the United States had built: wide roads, even in city centers, that seemed to invite speed. By the end of 2020 in New York, fatal accidents on these roads had arisen from the pre-pandemic era.

“We have a system that allows this incredible abuse, if the conditions are right for it,” Mr. Freemark said.

And that is precisely what the conditions were like during the pandemic. There was little congestion that held back reckless drivers. Many cities also reduced enforcement, closed DMV offices and offered reprieves to drivers who had unpaid tickets, expired driver’s licenses and out-of-state tags.

The pandemic has made it more apparent how much America’s infrastructure contributes to dangerous conditions, in ways that cannot easily be explained by other factors.

“We’re not the only country consuming alcohol,” said Beth Osborne, director of advocacy group Transportation for America. “We are not the only country with smartphones and distractions. We were not the only country affected by the global pandemic.

Instead, she said, other countries have designed transportation systems where human emotion and error are less likely to produce deadly results on the roads.

What the US can do to change that is obvious, supporters say: like fitting trucks with side underride guards to prevent people from being pulled under, or narrowing the roads that cars share with bikes. so drivers understand that they need to drive slower.

“We know what the problem is, we know what the solution is,” said Caron Whitaker, deputy executive director of the League of American Bicyclists. “We just don’t have the political will to do it.”

The bipartisan infrastructure bill passed last year takes modest steps to change that. There is more federal money for pedestrian and cycling infrastructure. And states will now be required to analyze deaths and serious injuries among ‘vulnerable road users’ – people outside cars – to identify the most dangerous traffic lanes and potential ways to fix them. .

States where vulnerable road users account for at least 15% of fatalities must devote at least 15% of their federal safety funds to improvements that prioritize these vulnerable road users. Today, 32 states, Puerto Rico and the District of Columbia face this mandate.

The larger question is whether Americans are ready to stop being exceptional in the world in this way.

“We need to change the culture that accepts this level of death and injury,” Ms Trottenberg said. “We are horrified when State Department employees lose their lives overseas. We need to create that same sense of urgency when it comes to road deaths.