What is our “cultural heritage” and why does it need protection? Stephen Stenning of the British Council responds.

There is a saying that culture and cultural heritage “shape” us. Can you explain?

Being British, Scottish, Londoner or Cornish is not about genes or blood. It has something to do with our environment and our history. We construct our identities from stories, objects and buildings that evoke the past of our ancestors: their glories, their tragedies or simply their daily lives. When people describe an impressive historic site, they often imagine the people who once passed through its gates, worshiped under its roof, gawked at its statues, or picnicked near its walls. A multitude of people have come before us and shaped the world we live in today.

Can you give an example of how the culture around us influences who we are?

A few years ago, I took around fifteen teenagers from London to an international festival in Türkiye. They participated alongside other groups from around forty countries. Upon their arrival, someone observed that although each of the young Londoners appeared to have a different ethnic background, with different hair colors and skin tones, they were recognizable as a group by their behavior. All were relatively shy, reserved and socially unadventurous. What I mean is that these were a group of young people whose families had arrived in London by different routes and from different places. Yet they were all identifiable as Londoners, because they had been shaped by the same things.

How have people tried to protect their cultural heritage in the past?

People will go to extraordinary lengths to protect valuable heritage in times of war or conflict. As a child I remember being taken to the historic Welsh mining town of Blaenau Ffestiniog looking for a steam railway and marveling at the slate gray slag heaps. Apparently, the slate mines housed specially constructed top-secret storage buildings that hidden thousands of works of art and precious objects during WWII. The intention was to ensure that our cultural assets would not fall into Nazi hands in the event of an invasion of the United Kingdom. As the The National Gallery was then bombed During the Blitz on London in 1941, this proved to be a very wise decision.

A more recent example can be found when January 2011 uprising in Cairo’s Tahrir Square, when revolutionary fervor and the withdrawal of police provided an ideal opportunity for looters. From the first night of riots, young activists formed a human chain around the National Museum which borders the square, helping security guards protect the treasures there.

What is the Hague Convention and what does it have to do with it?

THE Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict was developed in 1954 in response to the destruction of heritage and cultural property during the Second World War. Since then, more than 120 countries have joined all or part of the convention. But it’s only now that the UK is in the process of adopting it into law. In fact, the United Kingdom was the last major country to join this initiative.

Why did the UK take so long to sign up?

Questions have been raised in the past about the strength of the convention, and it may be that these questions have contributed to delaying ratification by the UK. The convention has been strengthened in recent years with the inclusion of criminal sanctions.

How much damage is being done to cultural heritage in countries where conflicts are ongoing?

It is a challenge to coordinate and collate records to get a complete picture of what has been damaged and destroyed, and to understand protection priorities.

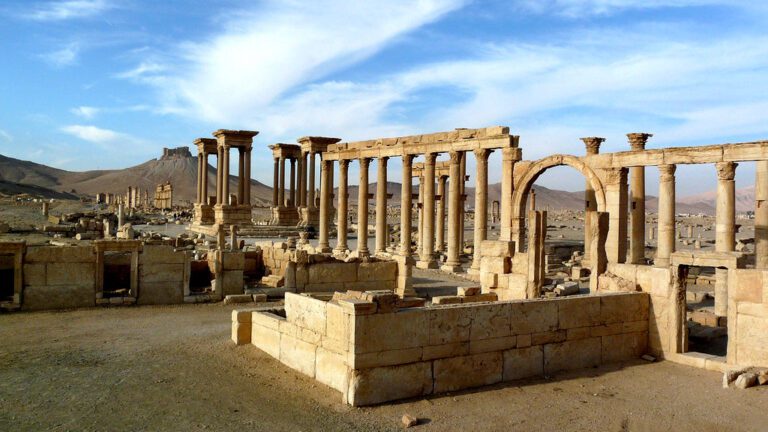

Newspaper headlines have focused on attacks on world heritage sites, such as the ancient city of Palmyra in Syria. In 2015, the Temple of Baalshamin and the third century Roman Triumphal arch were exploded by what we call Islamic State fighters. Images of Militants destroy exhibits at Iraq’s Mosul Museum with maces and axes was widely shared and disseminated.

However, the harmful effects of the conflict go far beyond the most famous sites and what can be seen in extremists’ propaganda images and videos. A renowned academic recently showed me before and after photos of an archaeological site in Iraq. In the next photo, the entire site was riddled with thousands of holes, carelessly drilled by looters looking for items to sell. It is a striking and alarming illustration of the dual impact of the conflict: first, the suppression of law and order, and second, the accompanying sense of despair, fueled by poverty, hunger and fear. It is unclear how much value was recovered from the site. It’s unlikely that anything the looters found would have earned them more than a few dollars, but the site itself was damaged beyond repair.

What will change now that the convention will be ratified by the United Kingdom?

This will involve many changes. For example, this has very direct implications for the Department of Defense. On 18 May 2016, the Secretary of State announced in the House of Commons that, as part of the ratification process, the British Armed Forces would establish a Military Cultural Protection Group. Military personnel, police and border agencies will need to be trained in cultural protection issues and the illicit antiquities trade, so they can recognize and understand what needs to be protected and where key sites are located. And on a general symbolic level, it indicates that the UK wants to understand and respect different cultures, helping them protect their heritage and property.

Do the British public widely support this decision?

The United Nations’ description of the destruction of Palmyra as a war crime » was picked up by almost every major British newspaper. With Palmyra we are talking about a World Heritage Site. The important point about these sites is that they are, according to the UN, “of exceptional cultural importance to the common heritage of humanity”. Their preservation and protection are important for humanity as a whole; they are part of our collective history. Stonehenge is not only important to people who live in or around Salisbury Plain, where the prehistoric monument is located. Its protection is not just the responsibility of local Wiltshire County Council. Its destruction will never be considered a simple local, or even national, issue. It would be a crime against humanity that would impoverish everyone on the planet.

UK organizations can currently apply for grants available through the Cultural Protection Fund carry out projects in a series of conflict-affected countries.