Yet regardless of Draper’s talent or pedigree, admission to the state bar was out of reach, the exclusive preserve of white men.

Instead, Draper followed another path. In October 1857, he presented himself to the judge Zacheus Collins Lee, Robert E. Lee’s first cousin and himself a slaveholder, who tested Draper’s legal knowledge and examined his qualifications.

“I found him intelligent and knowledgeable in his answers to the questions I asked, and qualified in all respects for admission to the bar of Maryland, if he were a free white citizen of this State,” Lee wrote .

Draper followed Lee’s recommendation and, at age 23, set sail for the fledgling African nation of Liberia.

On Thursday, Draper was posthumously admitted to the Maryland bar during a special session of the state Supreme Court. In what might seem like a surprise, the driving force behind the event — and similar acts of restorative justice nationwide — is a white law firm partner in Texas with a passion for history black people.

“At the time Draper was doing this, there were only about a half-dozen black lawyers in the United States,” said John G. Browning, 59, who traveled to Annapolis to file the formal motion for Draper’s admission to court. “And for him to think that that was a possibility was bold and daring and a testament to the potential that he had.”

Browning grew up in the 1960s and 1970s in Teaneck, New Jersey, not far from New York. After attending an elite, predominantly white Catholic school, he went to Rutgers University in New Brunswick, New Jersey, and his world opened up. He grew close to his black roommate and loved being surrounded by peers from different backgrounds.

“I had the benefit of taking black history classes there,” said Browning, a history major. “It occurred to me that much of this history had been hidden or overlooked from us. …There were so many things that I felt needed a broader audience.

Browning then graduated from the University of Texas Law School, settled in Rockwall, Texas – a largely white Republican town outside Dallas – and worked for a law firm.

In 2006, still researching black history, he wrote a column for a Rockwall newspaper in which he shared his discovery of the 1909 lynching of Anderson Ellis, an African-American farm worker, in the town. He concluded: “When we fail to educate our children about the barbarity wrought by the bigotry of our past, we do nothing to emerge from the lingering shadow it casts over our present. »

Browning was the target of hate mail and racist insults from people who thought he was black. But he also made a friend: Rockwall resident Carolyn Wright-Sanders, an African-American judge who would later become chief judge of the Fifth District Court of Appeal from 2009 to 2018. (She later mentored Browning when he was temporarily appointed to the appeals court in 2020.)

The two bonded over their love of history and co-wrote an article for the Howard (University) Law Journal on Texas’ first black lawyers; this, in turn, led to joint presentations across the state. Browning expanded his research to other states. Black bar sections and law students began asking him to speak about what he had learned.

Then came the summer of 2020. Browning gave a presentation on JH Williams, a black man who was denied admission to the Texas bar in 1882 because of his race. He previously wrote an article in the Dallas Morning News urging the Dallas Bar Association to push for restorative justice for Williams; nothing happened. But in May, after the killing of George Floyd by Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin, “I found a much more receptive audience,” Browning said.

In October 2020, the court joined only a handful in U.S. legal history to grant admission to the state bar posthumously on racial grounds.

After Draper, he hoped to secure the posthumous admission to the New York bar of Ely Parker, a Seneca Native American and Union Army general who served as his tribe’s legal champion. Parker was not allowed to take the bar consideration because many Native Americans did not become U.S. citizens until 1924.

“I hope to do one every year until I run out of crusades,” said Browning, who is also a law professor.

Earlier this year, Browning published an article in the University of Baltimore Legal Forum about Draper and Everett J. Waring, who in 1885 achieved what Draper could not: gain admission as the first black lawyer to the Maryland Bar.

Maryland Supreme Court Chief Justice Matthew Fader was present when Browning presented his findings at a symposium.

“And all of a sudden,” Browning said, “I found another receptive audience.”

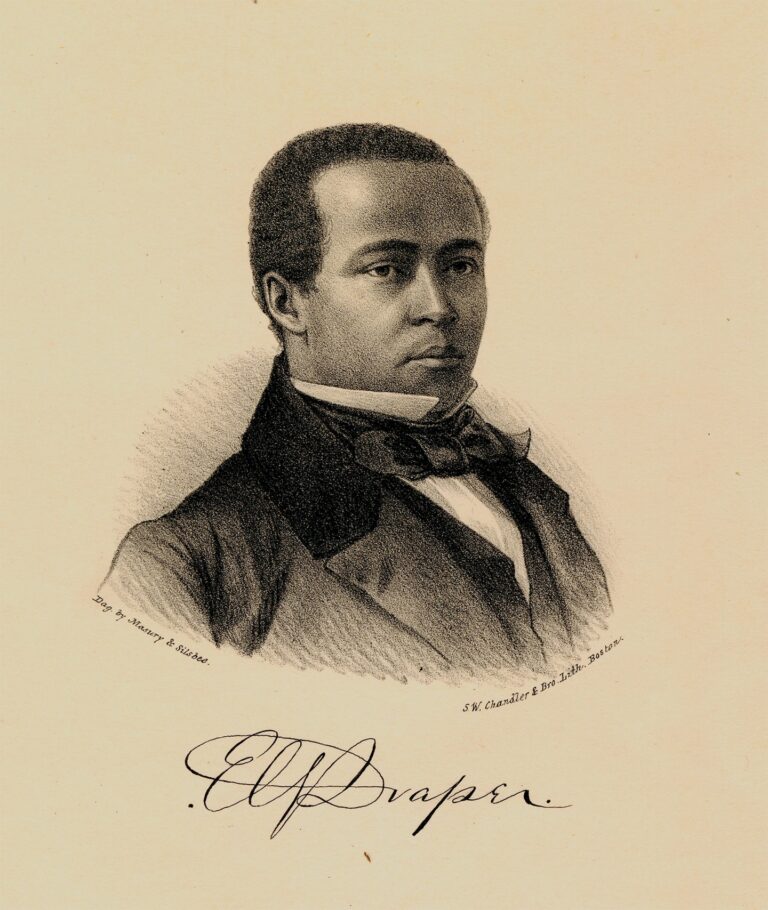

Draper was born in Baltimore in 1834 to Garrison Draper, a successful Baltimore tobacco merchant and cigar manufacturer, and his wife, Charlotte. As a free black man, the elder Draper had some education but wanted much more for his only son, Browning wrote in the Law Forum article.

Garrison Draper, skeptical that black people would ever enjoy freedoms equal to those of white men in the United States was attracted to the work of the Maryland Colonization Society.

Before 1932, the state had supported the work of the American Colonization Society, which urged African Americans to immigrate to an African colony that would later become the independent nation of Liberia. Maryland decided to go its own way, ultimately supporting an enclave of free and formerly enslaved black residents of Maryland, known today as Maryland County in Liberia.

While most blacks rejected colonization efforts, distrusted the motives of white defenders, and preferred to improve the country to which their families had been forcibly brought, the elder Draper became a correspondent for the Maryland Colonization Journal and believed that his son could have a free and free life. a dignified life outside the United States.

He sent young Edward to Philadelphia for a better public school education, which enabled him to pass the Dartmouth entrance exam requiring knowledge of subjects such as geography, Greek, and Latin. After earning high grades, he decided to become a lawyer, Browning wrote.

There were only a handful of law schools in the country before the Civil War, and Maryland had none. Most lawyers have been trained under the guidance of an experienced lawyer or judge. This was a challenge for Draper: There were only five black lawyers practicing in the United States at the time, and Draper probably assumed that in a state where African Americans were not allowed to be lawyers , there would be no willing white mentors. (Maryland resisted admitting African Americans to the bar long after the Civil War, falling well behind many Southern states, Browning notes.)

The Maryland Colonization Society supported Draper’s ambition, providing a member who was a retired Baltimore lawyer to serve as the young man’s legal guardian. The company’s general agent later called Draper a man of “amiable character, very modest and… a good student,” Browning wrote.

Draper then studied in the Boston office of the prominent Harvard-educated attorney Charles W. Storey, who was about to show him the court in action.

In 1857, Draper appeared before Judge Lee.

He seemed to have no illusions about his future in the United States. Six days later, he boarded the MC Stevens in Baltimore with his new wife, determined to become the first licensed and trained lawyer in Liberia.

Like his father, the Maryland Colonization Society had pinned its hopes on Draper. “It seems that there should be a regularly trained lawyer in a community of several thousand people, in a Republic of Liberty,” noted one writer in an article in the society newspaper, adding: “We do not We have no doubt that they will welcome Mr. Draper as one of those lawyers. of their fraternity.

Yet Draper’s great promise was not fulfilled. Barely a year after arriving in Monrovia, he died of tuberculosis, just shy of his 25th birthday. He left no descendants.

The tragic end of the young lawyer’s life still haunts Browning. Draper should have lived to lead the way, he said.

However, Browning hopes Draper will be posthumous Admission to the Maryland Bar helps people realize “that justice delayed is not necessarily justice denied.”

He added, “There is no expiration date for justice.”