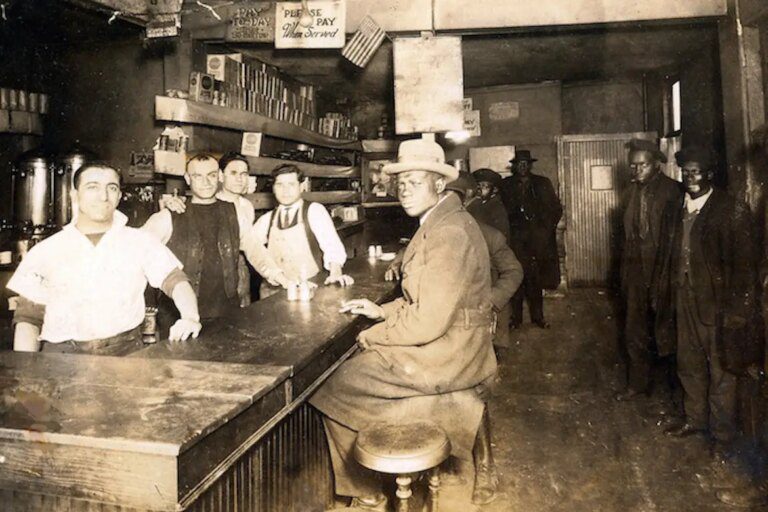

When Johnny Otis (1921-2012), legendary rock & roll musician, fled to Reno, Nevada, in 1941 with Phyllis Walker, his high school sweetheart, they were fleeing a California law preventing their love. From the state’s perspective, Otis, born Ioannis Veliotis to Greek immigrant parents, was considered white. Consequently, he was prohibited from marrying Phyllis, of Afro-Samoan ancestry, due to the infamous miscegenation laws which at the time prohibited interracial marriage. The couple managed to get around this problem in Reno.

We know how this scenario played out within the Veliotis household, thanks to Otis’ autobiography. Opposing the union, her mother sent her husband to Reno to annul it. Otis was a minor and she claimed she was exercising her parental rights. But his father objected to his wife’s objection. After meeting the couple, he took Phyllis “in his arms, hugged her and kissed her. “Your mother sent me to cancel the wedding, but I came to meet my new daughter,” he said in Greek, with tears in his eyes. ‘And besides, I don’t want God to come after me.’ “I never loved that old man more than I did that moment,” Otis exclaimed. Bridges have been built across the “color line” and between generations.

Otis became a civil rights activist. He opted for active citizenship, committed to advancing American ideals and opposing those who violated them. The Veliotis family drama provides a fitting introduction to the broader history of interactions between Greeks and black Americans. There can be no generalization. One is either anti-racist or racist. No in-between.

Our contemporary times call us to take sides with civil rights and the Black Lives Matter movement. Empowered by civic principles, America’s ethnic groups have joined the national debate in decisive ways. “Every Jew must decide which side he is on,” call the American Jewish media. Greek-American secular organizations and the Greek Orthodox Church have also taken a stand. In a must-read essay in the online newspaper Public OrthodoxyScholars of Christian Orthodoxy recognize the existence of systemic racism and how European Americans, including Greek Americans, have benefited from it.

The idea of active citizenship is important to our community. Being an active citizen is much more than voting and waving the flag of a country or party. Citizenship, among other things, means educating oneself about history and society. Exercise critical self-reflection.

What do we know about interactions between Black and Greek Americans? How well do we understand each other? The subject is under-researched and poorly understood. We wonder about the reasons for this neglect.

There have certainly been lasting friendships, camaraderie, intermarriage, collaborations and political alliances. But also distrust, ambivalence and resentment, often fueled by stereotypes and cultural myths that encourage, by political calculation, divisions and animosity between white Americans and people of color. To understand these issues, it is necessary to look beyond our personal experiences and assumptions and read widely about the place of race in American history.

One of these myths is that of equal opportunity. If one is interested in learning more, for example, about how the postwar social structure favored white European American men over white women and black Americans, I recommend Karen Brodkin’s very accessible book “How Jews Became White and What It Says about Race in America.” A significant body of literature addresses the ways in which systemic racism favored immigrants from southeastern Europe and their descendants. In the long list of books contributing to this historical understanding, I will cite the superb “Working Toward Whiteness: How America’s Immigrants Became White” by David Roediger, and “Roots Too: White ethnic Revival in Post-Civil Rights America” by Matthew Frye Jacobson . There is much more to do, and obviously even more to learn. Educating ourselves is part of our obligation as citizens.

Active citizenship is acquired by speaking And TO DO. There are notable examples of Greek Orthodox leaders as well as Greek-American writers and scholars who have openly addressed the issue. They did so at considerable professional and personal cost, particularly when it was dangerous or unacceptable to speak out against racial and social injustices.

Our emblematic Greek Orthodox figure of interracial solidarity is, of course, Bishop Iakovos. His legacy continues to shape Greek Orthodox and Greek-American civic activism today. Various initiatives cultivate civic ties with Black Americans.

I will never forget a particular example of Iakovos’ action as a citizen. That’s when he minced no words in rebutting the vocal opposition he heard from within his own community about his stance on civil rights. Although on an individual level there have been instances of cooperation and friendship between the Black and Greek-American communities, there have also been manifestations of racism. And black Americans were also aware that groups in the southeastern European American community were internalizing and perpetuating American racial hierarchies, often for their own benefit. It was their Faustian deal of acceptance – often out of fear – and it was the reason for their reluctance to rock the Jim Crow boat. Iakovos boldly expressed a sociological truth.

His example could serve as another lesson on how to express Greek-American citizenship today: the importance of speaking honestly about our history and social realities. This is what confident American ethnic groups do. Promote knowledge, reflect and debate. This openness is part of American Jewish philosophy. Italian-American institutions are also active in this direction. If American society examines its past and present, why can’t we? After all, we are dedicated American citizens. We are proud of our high educational achievements.

I enjoy history and sociology for helping me understand the social world beyond my personal experience. Regarding our topic, it is important to examine how individuals deal with the relationship between Greeks and Black Americans. But it is also necessary to consider the broader social structure within which this relationship plays out.

It is true that many Greek-Americans were discriminated against and humiliated and excluded from certain sectors of white society. Our businesses were boycotted by the Klan. Yet it is now a truism in mainstream academic circles that the experience of Southeastern Europeans cannot be compared to the systemic racism to which Black Americans have been subjected throughout America’s history.

Returning to the story of Johnny Otis, Otis became increasingly estranged from the community due to the community’s lack of support for his civil rights activism. How do we speak to the next generation, especially those seeking greater racial and social justice within our union? We need a new language.

In the days following the killing of George Floyd, I followed the rigorous manner in which American Jews mobilized their educational resources to confront the issue of institutional racism head-on. The quality of the conversation is astonishing. Intellectuals, scholars, authors, journalists, and leaders produce sophisticated self-reflection on the values and future direction of the community. I greatly admire and respect this achievement, and am inspired to work even harder to continue to bring the public a historical and sociological understanding of Greek America.

But for us to accomplish this new direction, broader participation is needed to reorient our public conversation. We found comfort and purpose in a popular narrative, which links ethnic socioeconomic success to pride and, via that pride, to cultural preservation. We often revert to idealizations, at the expense of a historical understanding of our community. It’s practical, but it doesn’t advance our civic consciousness.

There is a need to open a conversation about what it means to be a Greek-American citizen – someone who is knowledgeable and who fights to uphold justice for all – and this of course relates to the type of America, and Greek America, which we want. to help shape.

We cannot achieve this orientation without promoting the understanding of Greek America in the humanities and social sciences, the value of which we have not always appreciated. This is a new goal to inspire institutions and individuals who are currently advocating a Greek-American civic consciousness. Citizenship is about saying and doing, as I mentioned. This investment in Greek American studies will provide us with the new language we so urgently need to shape our civic and cultural future.

About the Author

Giorgos Anagnostou is editor-in-chief of Ergon, a peer-reviewed journal that promotes the arts, letters, and scholarship of Greek America. Anagnostou is a professor in the Department of Classics at Ohio State University and his areas of expertise include modern Greek culture and identity, the Greek diaspora, and American ethnicities.

Would you like to add your voice to the Pappas message?

This article is part of our Voices section which aims to broaden conversations in our community and allow people to share what they think. These articles do not in any way reflect the position or opinion of the Pappas Post and the inclusion of any article does not reflect the affirmation or denial of any particular point of view. Rather, we seek to provide people with a platform to share their views.

Interested in submitting your article? Read our guidelines and submit your content today.

Is the Pappas Post worth $5 a month for all the content you read? Every month we publish dozens of articles that educate, inform, entertain, inspire and enrich the thousands of people who read The Pappas Post. I ask those who frequent the site to chip in and help keep the quality of our content high – and free. Click here and start your monthly or annual support today. If you choose to pay (a) $5/month or more Or (b) $50/year or more then you will be able to browse our site completely without advertising!

Click here if you would like to subscribe to the Pappas Post’s weekly news update