The exhibition Facing the rising sun: Freedman Cemetery opened in 2000 at the African American Museum in Fair Park, telling the story of the thriving black community just north of today’s downtown. Curators Phillip Collins and Alan Govenar expected the exhibition to last only a year.

Two decades later, it is still on display. It serves as inspiration for two new exhibitions in adjoining exhibition halls, Central Trail: Deep Ellum Crossroads And See a blind world, a lemon never seen before, which opened last week and commemorates the 150th anniversary of the historic district. Both, again, are organized by Collins, a curatorial advisor and former museum staffer, and Govenar, founder of Dallas-based Documentary Arts and longtime chronicler of Deep Ellum.

“They are the result of this exhibition,” Govenar said, exploring the same themes of trauma, racism, violence, resilience and geography as the original exhibition. He also curated three companion pieces: When you go down into Deep Ellum And Unlikely Blues: Louis Paeth and Blind Lemon Jefferson at the new Deep Ellum Community Center; And Invisible deep elluman installation under the I-345 overpass that commemorates Black-owned businesses that were destroyed during the construction of the highway.

The highway replaced what was known as Central Track, the neighborhood’s main corridor of approximately seven blocks between Elm Street and Swiss Avenue. Govenar described it as full of life and diversity. It is a place where Jewish, Italian, Greek and other European immigrants joined freed slaves who “came together if not by choice, then by necessity.” For a city whose power structure often claimed membership in the Ku Klux Klan, it was a safe space, away (for a time) from conflict.

The exhibition highlights the reprehensible depiction of black life in the 1920s by Dallas Morning News, juxtaposing racist news clips with minstrel show posters from the same era. They’re all offensive, Govenar said, and that’s the point. But the subject is also a result of the limited representations of black life in the region.

Even if his book Deep Ellum: the other side of Dallasco-written with longtime journalist Jay F. Brakefield, has just appeared in his third edition by local publishing house Deep Vellumno additional photographs have emerged from collectors or archives.

“It’s astonishing,” he said.

The show tells the history of the neighborhood through press clippings from News and other newspapers. One clip is about white socialites dining out because their servants were celebrating Juneteenth.

“Articles with racist content could constitute a thesis,” he said.

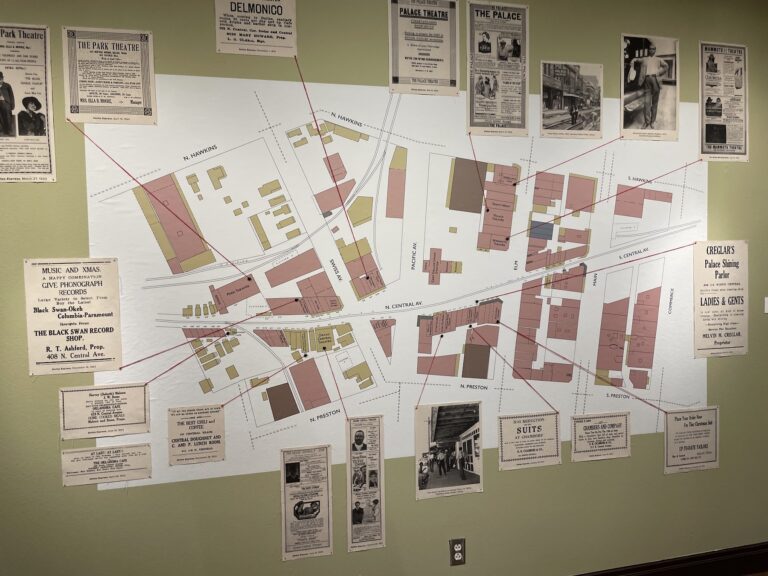

They also redesigned a map identifying key structures in the neighborhood, drawn from public records and newspapers. The map, articles, and clippings are printed on canvas rather than cardstock, representing the cotton that black slaves picked before emancipation.

At the center of the exhibition is a large abstract sculpture, created with a large rectangular wooden cross angled upwards from the ground, along a noose. Collins, who helped build the museum’s extensive and famous folk art collection, said it represents the “fall of Central Track.”

The cross is a metaphor for its unintended decline when the North Central Expressway and I-345 destroyed it in the 1940s.

Small shapes lining the wood represent homes and other structures that were lost, leading to the displacement of the community. The noose, he added, also recalls the lynching of black people in Dallas.

Across the hall, in another exhibition space, “Seeing a World Blind Lemon Never Saw” is a conceptual exhibit that documents the blues singer’s journey from southeast Texas to his eventual residency in Dallas. It complements a book of the same name, also recently published by Deep Vellum.

For three decades, Govenar photographed Lemon’s journey and documented what has and has not changed about the lands he once roamed. The large-print photographs trace the landscape from Wortham in East Texas to Dallas. It represents the world Blind Lemon would have liked to see, Collins said.

The exhibit is part of Govenar’s 36-year study of Lemon’s life, including a loose timeline from the time he was first buried in an unmarked grave to decades later, when the cemetery was named in his honor. It tells the story of a nearby church that was burned down and rebuilt by the attackers after their capture. There are older and newer houses in these photographs, as well as quirky religious signs – “HIGHWAY TO HEAVEN” – mounted on a caravan with an Israeli flag hanging next to it. (Govenar believes it was created by messianic Jews.) All are illuminated by precise lighting and each carries its own narrative. These stories may stray from the life Blind Lemon led, but still represent how the land has changed over time.

Collins said what connects the three shows is the idea of violation. “Central Track has been breached by the highway. These rural areas have been violated by oil and gas pipelines. And the cemetery has given way to developers.

As Deep Ellum celebrates its 150th anniversaryth year, new exhibitions seek to place its history at the center of the debate.