Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with information on fascinating discoveries, scientific advances and much more..

CNN

—

Not all science is done by people in white coats, under the fluorescent lights of university buildings. Sometimes the trajectory of the scientific record is changed forever in a pub over a pint of beer.

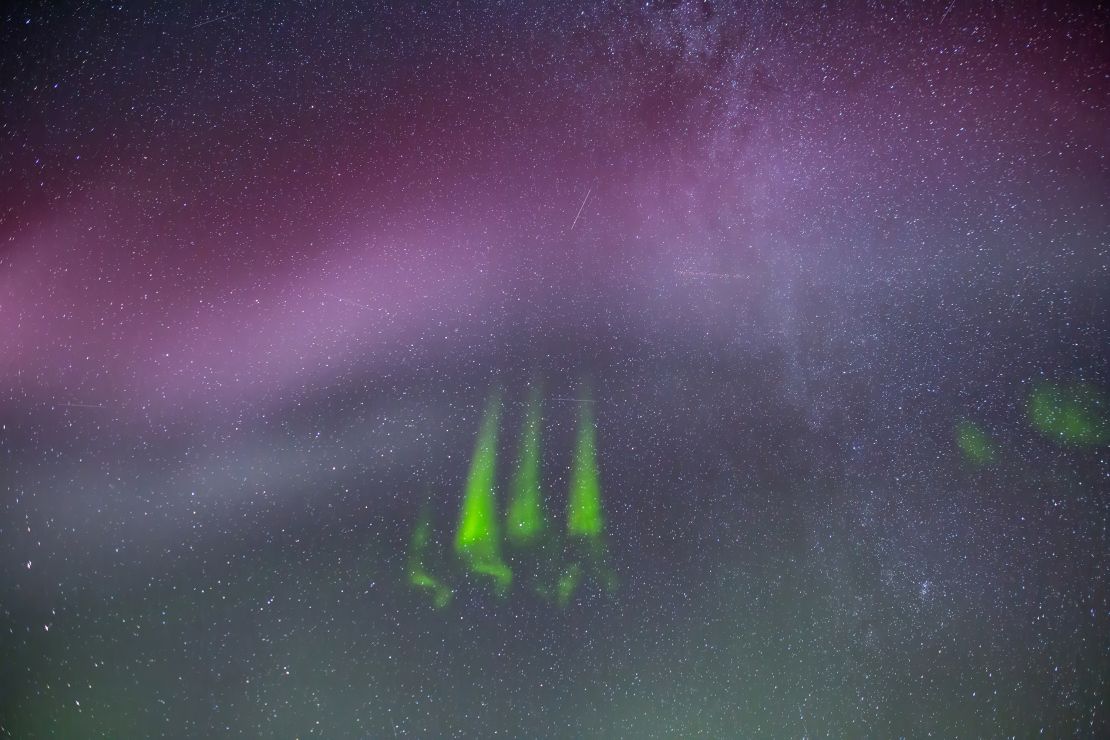

This is the case for the large purple and green lights that can hover above the horizon in the northern hemisphere. The phenomenon looks like an aurora but it is actually something completely different.

His name is Steve.

This rare light show has created a bit of a buzz this year as the sun is enter its most active periodincreasing the number of dazzling natural phenomena that appear in the night sky – and leading to new reports that people have spotted Steve in areas where he doesn’t usually appear, like parts of the United Kingdom.

But about eight years ago, when Elizabeth MacDonald, a space physicist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, was in Calgary, Alberta, for a seminar, she had never seen the phenomenon in person. And he didn’t have a name yet.

In fact, few scientists actively studying aurora and other night sky phenomena had witnessed a Steve, which appears closer to the equator as the Northern Lights and is characterized by a purple-pink arc accompanied by vertical green stripes.

After MacDonald gave a lecture at a nearby university, she met citizen scientists — mostly photographers who spend nights hoping to capture the next stunning image of colors dancing across the Canadian sky — at the Kilkenny Irish Pub .

“I had already reached out to local Alberta aurora hunters (in) a Facebook group, which was quite small at the time,” MacDonald said, “but very eager to share their observations and interact with The NASA.”

Photographers came with their photos in hand, eager to show off the mysterious light show they had captured.

At the time, “we didn’t know exactly what it was,” MacDonald said of the phenomenon shown in the footage.

Neil Zeller, a citizen scientist or photography expert – as aurora-chasing photographers are sometimes called – was present at this meeting.

“I started spotting what we called a proton arc in 2015,” Zeller said. “It had been photographed in the past, but misidentified, and so when I attended this meeting at the Kilkenny Pub… we started a little argument about (whether) I had seen a proton arc.”

Dr. Eric Donovan, a professor at the University of Calgary who was at the pub with MacDonald that day, assured Zeller that he had not seen a proton arc which, according to a later co-authored paper by Donovan, is “subvisual, broad and diffuse,” while a Steve is “visually bright, narrow and structured.”

“And the conclusion of that evening was, well, we don’t know what that is,” Zeller said. “But can we stop calling it a proton arc?”

It was shortly after that pub meeting that another aurora chaser, Chris Ratzlaff, suggested a name for the mysterious lights on the group’s Facebook page.

The members of the group were is working to better understand the phenomenon, but “I suggest we call him Steve in the meantime,” Ratzlaff wrote in a February 2016 Facebook post.

The name was borrowed from “Over the Hedge,” the 2006 DreamWorks animated film in which a group of animals are frightened by a towering leafy bush and decide to name it Steve. (“I’m a lot less afraid of Steve,” says a porcupine.)

The name stuck. Even afterwards, the phenomenon could be better explained. Even after explanations about Steve began to take shape in scientific articles.

Scientists then developed an acronym to accompany the name: Strong Thermal Emission Velocity Enhancement.

And this meeting in a small Canadian pub was a turning point.

“It was the in-person meeting that was one of the things that gave it more momentum to ultimately collect more and more observations in an increasingly rigorous way so that we could correlate them with our satellite,” MacDonald said.

Eventually, MacDonald said a satellite directly observed Steve, collecting crucial data and leading to a 2018 study this suggested that the lights were a visual manifestation of something called subauroral ion drift, or SAID.

SAID refers to a narrow stream of charged particles in Earth’s upper atmosphere. Researchers already knew SAID existed, MacDonald said, but they didn’t know it might be visible from time to time.

Steve is visually different from auroras, which are caused by electrically charged particles that glow when they interact with the atmosphere and appear as dancing ribbons of green, blue, or red. Steve – if it is caused by SAID – is made up of essentially the same elements. But it appears at lower latitudes and appears as a streak of purple light accompanied by distinctive green bands, often called palisade.

Steve can be frustrating and difficult to spot, appearing alongside auroras with little regularity. Sometimes spotting Steve It’s a matter of luck, noted Donna Lach, a photographer based in the Canadian province of Manitoba.

Lach has seen and photographed Steve about two dozen times, a rare feat in the world of sky photography. She said she uses her family farm located on remote land in southern Manitoba, where there is little to no light pollution.

She always checks the space weather before leaving. It looks for conditions at least Kp3 – a space weather index ranging from Kp0 to Kp9, with higher numbers indicating greater activity.

It appears, Lach said, that the phenomenon begins with the SAR arc – a stable auroral red arc – which appears near the auroral oval.

“It may eventually migrate south…toward the equator side of the aurora and form a Steve,” Lach said.

A Steve will always appear next to an aurora, Lach and Zeller said, but not every aurora includes a Steve.

Where and how to see Steve

The Earth is entering a period of enhanced solar activityor solar maximum, which occurs about every 11 years, MacDonald said.

Meanwhile, viewers can expect more visible light shows in the sky and, potentially, the chance to observe a low-latitude Steve. Bright phenomena have been observed as far south as Wyoming and Utah, she said.

“There have been storms recently that have been visible in the United States – just a little bit – to Death Valley,” MacDonald said. “And recently the November one… was visible at its southernmost point over Turkey, Greece and Slovakia, and even China, which is very rare. »

However, Steve is best seen through the lens of a camera.

To the naked eye, it may appear as nothing more than what looks like a faint contrail from a plane crossing the sky, Zeller and Lach noted, and can be easy to ignore.

The cameras are much more sensitive to light and capture Steve’s vibrant colors through their lenses.

Even a phone camera can work, MacDonald added.

“This is the first solar maximum, I would say, where most people’s cell phones can take a good photo of the aurora,” she said.

The Steve phenomenon is most likely to be captured around the spring and fall equinoxes, according to Zeller and Lach. (This year’s autumnal equinox occurred on September 23.)

“I don’t think it’s Steve that occurs the most during the equinox, but it is well known that larger aurora storms occur closer to the equinoxes,” MacDonald noted. And since Steve tends to appear alongside the aurora, the phenomenon might be more likely to be seen in March or September.

Zeller and Lach said they usually saw Steve between evening and midnight.

“It’s not an all-night affair,” Zeller said. “The longest I saw Steve was an hour from start to finish.”

Zeller added that he waits until an auroral storm begins to diminish before turning his camera east — from his vantage point in Canada — or directly upward, then “you start to see this purple river “.

It’s Steve.

MacDonald encourages anyone interested in photographing the Northern Lights – or a Steve – to get involved in online communities. Aurorasaurus, A website which connects photographers with scientists, is a project close to his heart, highlighting his crucial role in helping scientists formally identify Steve.

Photos provided by the public are constantly helping scientists improve their understanding of these light shows, she said.

“Scientists are not as good aurora chasers as the enthusiast public,” she said. “We don’t stay up all night and we’re not photographers either.”