In the spring of 585 BC, in the eastern Mediterranean, the moon appeared out of nowhere to obscure the face of the sun, turning day into night.

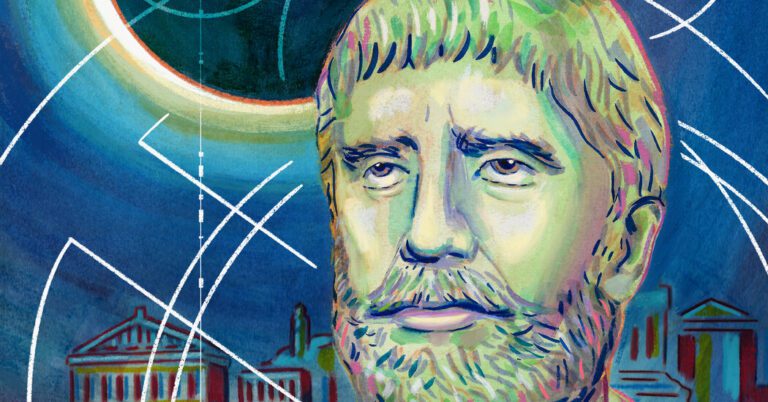

Back then, solar eclipses were shrouded in frightening uncertainty. But a Greek philosopher is said to have predicted the disappearance of the sun. His name was Thales. He lived on the Anatolian coast – today in Turkey but then the cradle of early Greek civilization – and was said to have gained his unusual power by abandoning the gods.

The eclipse had an immediate impact on the world. The kingdoms of the Medes and Lydians had been waging a brutal war for years. But the eclipse was interpreted as a very bad omen, and the armies quickly laid down their arms. The terms of the peace provided for the marriage of the daughter of the king of Lydia to the son of the Median king.

Thales’ impiety had a more lasting impact, his reputation soaring over the ages. Herodotus recounted his prediction. Aristotle called Thales the first man to understand nature. Classical Greece honored him as the first of its seven sages.

Today, the tale illustrates the ancients’ fear of the disappearance of the sun and their great surprise that a philosopher knew it in advance.

The episode also marks a turning point. For centuries, solar eclipses have been considered omens of calamity. The kings trembled. Then, about 2,600 years ago, Thales launched a philosophical initiative to replace superstition with a rational prediction of eclipses.

Today, astronomers can determine — to the nearest second — when the Sun April 8 will disappear throughout North America. Weather permitting, it is expected to be the most watched astronomical event in American history, astonishing millions of skywatchers.

“Everywhere you look, since modern times, everyone has wanted predictions” about what the heavens would have in store for us, said Mathieu Ossendrijver, Assyriologist at the Free University of Berlin. He said the Babylonian kings “were scared to death because of the eclipses.” In response, rulers scanned the skies in an effort to anticipate bad omens, appease the gods, and “enhance their legitimacy.”

Clearly, Thales was the originator of the rationalist vision. He is often considered the world’s first scientist, the founder of a radical new way of thinking.

Patricia F. O’Grady, in his 2002 book on the Greek philosopher, described by Thales as “brilliant, truthful and courageously speculative”. She described her great achievement as having seen that the fraught world of human experience results not from the whims of the gods but from “nature itself”, initiating civilization’s quest for its secrets.

Long before Thales, the ancient landscape bore traces of successful predictions of eclipses. Modern experts say that Stonehenge – one of the most famous prehistoric sites in the world, construction of which began around 5,000 years ago – could have helped warn of lunar and solar eclipses.

While the ancient Chinese and Mayans By noting the dates of eclipses, few ancient cultures learned to predict disappearances.

The first clear evidence of success comes from Babylonia – an empire in ancient Mesopotamia in which court astronomers made nocturnal observations of the moon and planets, usually in connection with the gods and magic, astrology and mysticism of numbers.

Departure around 750 BC, Babylonian clay tablets bear eclipse reports. Beginning in the eclipse ages, the Babylonians were able to discern the patterns of celestial cycles and eclipse seasons. Court officials could then warn of God’s displeasure and attempt to avoid punishment, such as the fall of a king.

The most extreme measure was to employ a scapegoat. The acting king performed all the usual rites and duties, including those of marriage. The alternate king and queen were then killed as a sacrifice to the gods, the true king having been hidden until the danger had passed.

Initially, the Babylonians focused on recording and predicting eclipses of the moon, not the sun. THE different sizes of eclipse shadows that they observe a greater number of lunar disappearances.

Earth’s shadow is so large that, during a lunar eclipse, it blocks sunlight from a huge region of space, causing the Moon to disappear and reappear. visible to everyone on the night side of the planet. The size difference reverses during a solar eclipse. The Moon’s relatively small shadow makes the observation of totality – the complete disappearance of the sun – quite limited in its geographic scope. In April, the path of totality over North America will be vary in width between 108 and 122 miles.

A long time ago, the same geometry reigned. So the Babylonians, through expediency, focused on the moon. Finally, they REMARK that lunar eclipses tend to repeat every 6,585 days, or approximately every 18 years. This led to major advances in predicting lunar eclipse probabilities, even though little was known about the cosmic realities behind these disappearances.

“They could predict them very well,” said John M. Steelehistorian of ancient sciences at Brown University and contributor to a recent book“Eclipse and revelation”.

It is into this world that Thales was born. He grew up in Miletus, a Greek city on the west coast of Anatolia. It was a maritime power. The city’s fleets established wide trade routes and a large number of settlements that paid tribute, making Miletus wealthy and a star of early Greek civilization before Athens rose to prominence.

Thales would have come from one of the distinguished families of Miletus, would have traveled to Egypt and maybe Babylonia, and having studied the stars. Plato said how Thales had fallen into a well one day while examining the night sky. A servant, he reported, teased the thinker because he was so eager to know the sky that he ignored what lay at his feet.

It is Herodotus who, in “The Histories”, said of Thales predicting the solar eclipse that ended the war. He said the ancient philosopher had anticipated the date of the sun’s disappearance “within a year” of the actual event – a far cry from today’s accuracy.

Modern experts, from 1864, cast doubt on the old claim. Many saw it as apocryphal. In 1957, Otto Neugebauer, historian of science, called it is “very doubtful”.

In recent years, this claim has received new support. The updates rely on knowledge of the type of observation cycles developed by Babylon. These models allow Thales to make solar predictions that, while not certain, could still be successful from time to time.

If Stonehenge could do it once in a while, why not Thales?

Mark Littmann, astronomer, and Fred Espenaka retired NASA astrophysicist specializing in eclipses, says in their book, “Totality”, that the date of the war eclipse was relatively easy to predict, but not its exact location. As a result, they to writeThales “could have warned of possibility of a solar eclipse.

Leo Dubal, a retired Swiss physicist who studies artifacts from the ancient past and recently wrote about Thales, okay. The Greek philosopher could have known the date with great certainty while being uncertain about where the eclipse might be visible, such as on the front lines of war.

In an interview and a recent test, Dr. Dubal argued that generations of historians have confused the enlightened intuition of the philosopher with the precision of a modern prediction. He said Thales understood perfectly, just as the ancient Greeks stated.

“He was lucky,” Dr. Dubal said, calling this kind of serendipity an integral part of the discovery process in scientific research.

Over the ages, Greek astronomers learned more about the Babylonian cycles and used this knowledge as a basis to advance their own work. What was marginal in Thales’s time became more reliable, including prior knowledge of solar eclipses.

The Antikythera Mechanism, a mechanical device of astonishing complexity, is a testament to Greek progress. It was made four centuries after Thales, in the 2nd century BC, and was find off the coast of a Greek island in 1900. Its dozens of gears and dials let it predict many cosmic events, including the dates of solar eclipses – but not, as usual, their narrow paths of totality.

For centuries, even until the Renaissance, astronomers continued to improve their eclipse predictions based on Babylonian pioneers. The 18-year cycle, said Dr. Steele of Brown University, “has a very long history because it worked.”

Then came a revolution. In 1543, Nicolaus Copernicus placed the Sun – and not the Earth – at the center of planetary movements. His breakthrough in cosmic geometry led to detailed studies of the mechanics of eclipses.

The superstar was Isaac Newton, the towering genius who, in 1687, unlocked the universe with its law of gravitational attraction. His breakthrough made it possible to predict the exact trajectories not only of comets and planets, but also of the Sun, Moon and Earth. As a result, eclipse forecasts have become more accurate.

Newton’s good friend Edmond Halley, who lent his name to a brilliant comet, exposed the new powers to the public. In 1714 he published a map showing the predicted path of a solar eclipse across England next year.

Halley asked observers to determine the true scope of totality. Scholars to call history’s first in-depth study of a solar eclipse. In precision, its predictions surpassed those of the Astronomer Royal, who advised the British monarchy on astronomical questions.

Today’s specialists, using Newton’s laws and banks of powerful computers, can predict the movements of the stars millions of years in advance.

But closer to home, they have difficulty making eclipse predictions over such long periods. This is because the Earth, Moon and Sun are relatively close together and therefore exert relatively strong gravitational pulls on each other, the strength of which changes subtly over the eons, slightly altering the rotations and positions of the planets .

Despite these complications, “it is possible to predict the dates of eclipses more than 10,000 years from now,” Dr. Espenak, a former NASA expert, said in an interview.

He created the space agency web pages which list upcoming solar eclipses – some of which almost four millennia from now on.

So if you’re excited about the whole April 8 thing, you might think about what awaits those living in what we now call Madagascar on August 12, 5814. According to Dr. Espenak, this date will feature the phenomenon of day. turning into night and back into day – a spectacle of nature, not of malevolent gods.

This is perhaps worth considering because, if for no other reason, it represents another testament to Thales’s wisdom.